Chapter 2: Suspicion and Survival

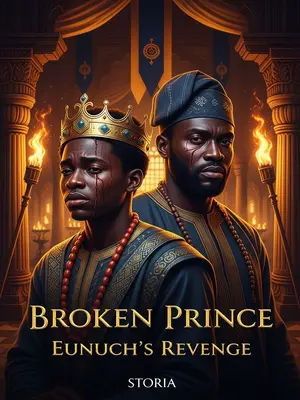

The third son, after he expose the whole plan, think say Chief Garuba go favour am. But Chief Garuba sharp, he see through the boy’s mind, come begin dey suspect all the sons even more. Garuba mind dey race—he remember when him own brother try am same way, that year wey papa die. For Chief Garuba eye, none of him sons dey trustworthy; all of dem just dey find how dem go chop chiefdom.

Chief Garuba no be novice for this kind matter. For his youth, he don see how brothers fit use sweet mouth scatter compound. When the third son dey kneel down dey greet am, Garuba just dey look am with one eye. Sometimes, he go call the boy, ask am to recite the ancestors’ praise names, just to see if he go shake. People for the compound begin dey avoid gossiping around the chief’s hut, because his ear long—any small wahala, he go notice. Women would say, “Hmm, this family matter fit scatter ground, make we dey waka jeje.”

From that time, Chief Garuba just withdraw, no dey trust anybody. The beef between the sons come worse pass before, everybody dey move like snake for the compound.

He stopped attending evening gatherings at the big ogbono tree by the village square, where elders dey gather after evening prayers, and no longer shared kola nut with the elders after prayers. The laughter wey dey flow from Chief Garuba stool don dry, like stream for dry season. Even the goats sensed the tension; they bleated restlessly at dusk. The wives tiptoed around, careful not to raise their voices, while the sons eyed one another, pretending to smile but always measuring each other’s steps. The smell of burning akara sometimes drift pass, but nobody get appetite. Rumours started flying—who dey visit the herbalist, who dey consult the dibia by moonlight. The compound wey before dey full of song now heavy with silence, only broken by the distant crow of the village rooster.

At the end, na only the fourth son, Ibrahim, wey keep quiet and endure everything, come out clean. The guy sabi say to win chiefdom, first you go survive. He just dey hold himself, no rush, dey observe, dey wait for correct time to make him move.

Ibrahim was not the type to chase shadows or gossip. He greeted everyone with respect, always quick to fetch water for his mother or help the old men cross the stream. People started to notice his patience. Even when they mocked him, saying, “See as he dey slow like tortoise,” he would just smile, nod, and keep his eyes low. He often visited the mosque quietly, never boasting about his prayers. In the evening, while his brothers plotted inside, Ibrahim would sit by the yam barn, counting the stars and listening to his grandmother’s old tales. Some neighbours started whispering, “Na this kind calm hand dey carry goat wey get stubborn horn.”

Na so the wahala for who go take over enter the last round, with the sons dey eye each other, nobody sure who go finally sit down for the chief’s stool.

The elders, tired but determined, began preparing for the final rites—the masquerades would soon dance, and the talking drums would call the whole village together. The town crier’s bell echoed every morning: "Make una ready! The time don near!" Even traders from neighbouring villages started arriving to watch who would be crowned. As the harmattan wind picked up, carrying dust and the scent of roasted maize, the compound felt poised for something big, each man’s heart beating its own secret rhythm, waiting for fate to choose the next chief. Even the ancestors, for their silent realm, dey wait—whose name go echo for the drums when the sun finally set?