Chapter 1: The Palm Wine Oath

The village talking drums thundered, and the whole Okoli family moved out in full force.

The sound carried far, shaking the early morning air. Even neighbours from other compounds poked their heads over the fence, murmuring among themselves, because Okoli talking drums no dey sound unless wahala don land. The men of our family, from elders with grey beards to young men just out of secondary school, all marched in their best George wrappers and well-ironed senator shirts, filling the compound with a sea of patterned Ankara and the aroma of camphor and shea butter. Women gathered in tight knots, whispering, eyes wide with worry, their hands clutching their heads in anticipation of what the day would bring. Some children, sensing the tension, clung to their mothers’ wrappers, peeking out from behind their legs.

Before the clan leader spoke, he poured a libation of palm wine on the red earth, murmuring prayers for guidance and justice. Then he held up a bowl of yellow palm wine, his voice strong and serious. "Twenty years ago, two area boys from the technical college stabbed a returning professor to death, nearly causing wahala in the whole city.

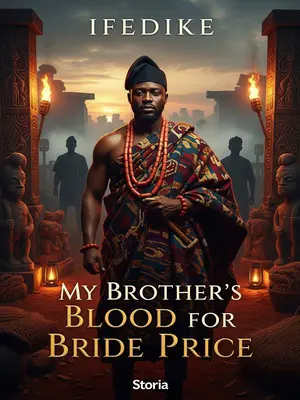

"Now, after twenty years, the Okoli clan’s ancestral council has spent heavily to bring Professor Ifedike back to Nigeria, to help guide the technological upgrade of our three hundred and fifty clan-owned factories.

"But just last night, he was slapped and robbed by one small area boy from technical college.

"That boy is underage, so they’ll soon release him. He even had the guts to threaten Professor Ifedike with revenge. Him dey craze? E think say Okoli people no get power?"

His words carried weight, each sentence falling heavy as a pestle pounding yam in a mortar. The crowd murmured, some clapping their hands in disbelief. The women hissed in outrage, some spitting on the ground to ward off evil. A few old men exchanged knowing looks, recalling the last time the family had gathered like this for blood matter.

He raised his bowl, his voice booming: "Today, we draw the lot of 'Ndụ na ọnwụ.'" In Igbo, that means life and death—whoever draws it, the whole clan will take care of his family, set up his own genealogy, and the clan will offer prayers and honour his spirit.

The elders behind him nodded in solemn agreement, their eyes sharp, fixed on the proceedings. The youngest among us shifted on our feet, trying to swallow the anxiety building in our throats. Above us, the morning sun threw golden light on the assembly, as if the ancestors themselves had come to bear witness.

The clan leader lifted his bowl and shouted: "Protect the Okoli clan for generations!"

The cry echoed, bouncing off the mud walls. The air vibrated with energy; a few men stamped their feet on the earth, as if to awaken the spirits of our forefathers. Even the goats in the yard fell silent, sensing the gravity of the moment.

All of us raised our bowls.

The crowd moved as one, a wave of hands lifting bowls aloft. Some men muttered short prayers—"God no go shame us!"—before gulping the wine. The elders raised theirs highest, eyes closed, lips moving in silent communion with their personal chi.

Three thousand strong men of the Okoli clan roared, their voices shaking the very ground: "Kill!"

The noise travelled far, startling birds from nearby almond trees. Children covered their ears. The women ululated, their voices weaving into the shout like old ritual. In that moment, there was no turning back. The clan had spoken. Blood would answer blood.

We all downed the yellow wine in one gulp.

The palm wine bit sharp and sweet, burning a trail down my throat, settling hot in my stomach. Some men coughed, wiping their lips with the back of their hands, eyes watering slightly, but nobody dared leave a drop in the bowl.

Only at the bottom of my bowl did I see the words: "Ndụ na ọnwụ."

The writing, done with a sliver of charcoal, stared up at me as if it had been waiting all along. My hands trembled a bit, but I kept my face blank—no room for weakness in front of the clan.

I smashed the bowl. Everyone’s eyes turned to me.

The sound rang sharp, fragments scattering at my feet. The silence that followed was heavy, the kind that makes your ears ring. Every face, from the youngest cousin to the oldest uncle, turned my way.

I wiped the wine from my lips and turned to leave.

My wrapper brushed my legs as people cleared road for me—like when big man dey waka. A few hands reached out, briefly brushing my shoulder or arm—silent gestures of respect and farewell. I kept my back straight, refusing to show fear.

"From today on, the ancestral hall will offer prayers to my spirit tablet."

The statement landed like a stone. The elders murmured their approval, while the women began to keen, some crouching to the ground, their cries rising to the sky. In the heart of the ancestral hall, I knew my name would be written alongside warriors who gave their lives for the clan.

For this life, some people heavy like Olumo Rock, others light like chicken feather.

It’s an old Yoruba saying my grandfather used to repeat, always with a sideways glance at my cousins who liked to run from work. Today, the words tasted like iron in my mouth. The elders nodded when I said it, understanding the weight of the proverb.

Professor Ifedike is as heavy as Olumo Rock—a true national treasure.

He left a million-naira salary to come back and build our country’s industry. In my heart, he is irreplaceable.

To leave abroad, with all the comfort and money, just to return to the dust and noise of Naija, only someone with a lion heart fit do am. Everybody knew what he sacrificed. Some of the younger boys had even tried to take selfies with him at the factory, calling him "baba tech."

I still remember how humble Professor Ifedike was. He never formed. He even shyly asked me to help him set up mobile banking, surprised at how advanced the country had become—no need for cash, just tap your phone to pay.

He treated all of us like brothers. Even when he fumbled with his phone, pressing the wrong app, he would laugh and scratch his head, saying, “Na wah, this thing pass me o.” But he learned quickly. I was proud to show him, feeling important for once.

He pat my back, say e glad to dey home, even though wahala plenty, and had already discovered many problems in our factory area.

His eyes always lit up when talking about improvements. He would squat by the generators, chatting with mechanics, or join the women frying akara for lunch, asking questions about every step. You could see he genuinely cared.

But his injury is linked to me.

It’s my fault. I was busy delivering equipment to the clan’s factory, and we agreed I’d help him set up mobile banking after my holiday.

Guilt knotted my stomach each time I remembered. All the time I wasted, thinking it could wait. If only I had not postponed, maybe all this mess would have been avoided.

If not for me, Professor Ifedike wouldn’t have had to pay with cash, and wouldn’t have been targeted by that area boy.

Regret be like bitter kola—no matter how you try, the bitterness no go comot. Every time I close my eyes, I see his gentle smile as he handed over crumpled naira notes, not knowing what danger lurked close by.