Chapter 4: Promises of Justice

It’s the kind of place where everyone knows everyone, where you wave at neighbors and trust folks you’ve never met. Lillian probably thought nothing of it—just another friendly face.

Tyler successfully struck up a conversation with Lillian and learned that she was home alone with the child during the day—her husband was at work.

He asked casual questions—"Your husband at work? Just you two today?"—and Lillian answered without hesitation. She had no reason to be suspicious.

Lillian had bought groceries and daily necessities, so Tyler offered to help carry her things.

He grabbed a couple of bags, smiled, and said, "Here, let me give you a hand." It was a small gesture, the kind that happens a hundred times a day in small towns.

Maybe because it was hard to manage the stroller and the shopping bags at once, she accepted his help, allowing him to enter her home.

She hesitated for just a second, then nodded, grateful. He followed her up the stairs, chatting about the weather, the price of diapers, anything to seem normal.

“I helped her carry the things in, went inside, locked the door, then... I pulled out a knife, threatened her, told her to go into the bedroom or I’d kill her daughter. She was so scared, she did whatever I said...”

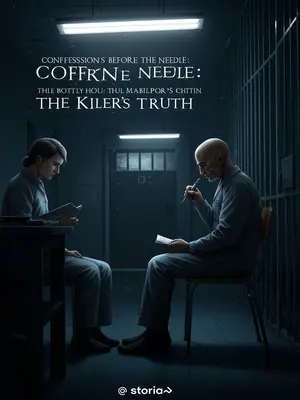

His words were cold, matter-of-fact. No emotion. No regret. I could see Harris’s jaw clench. Tyler described the scene as if he were reading from a script, no emotion, no regret.

“If she didn’t resist, why did you still kill them?”

Harris asked the question we were all thinking. Tyler looked down, picking at his cuffed wrists.

“She did resist, she fought back. When I told her to lie on the bed... she resisted... it was her fault, if she hadn’t resisted, would I have hit her? I was also afraid someone would hear her. When I came to my senses, she was already dead...”

He said, “It was all her fault.”

The words made my blood boil. Blaming the victim, refusing to take responsibility—it was the oldest, ugliest excuse in the book. I wanted to reach across the table, but I forced myself to stay still.

Anyone hearing this would feel their blood boil.

Harris’s knuckles were white. His voice was tight. I could see the rage in his eyes, but he kept his tone even. We had to do this by the book.

But we clenched our teeth and suppressed the urge to hit him—there were cameras in the interrogation room.

The red light on the camera was a constant reminder: no matter how bad we wanted to hit him, we couldn’t. Everything was being recorded, every word, every gesture.

“And the baby? Why did you have to kill the baby too?”

I asked the question quietly, almost afraid of the answer. Tyler stared at the floor, voice barely above a whisper.

“She cried—wailed and screamed—who could stand that? I panicked; the woman had just died, I was nervous, and the baby kept crying. Can you blame me? So I... put her in the trash bag, she kept crying, so I slammed her a few times, then she stopped... then I left...”

He recounted all this in a flat, casual tone.

It was as if he were describing a minor inconvenience. Not the murder of a child. The lack of emotion was more chilling than any outburst could have been.

Two lives—a mother and her daughter—who could have had a beautiful future.

I thought of Savannah’s smile in that family portrait, of Lillian’s laughter. All of it gone, snuffed out in a moment of senseless violence.

He didn’t even think he had done anything wrong.

He shrugged, as if the whole thing was just bad luck. There was no remorse, no understanding of the pain he’d caused.

Since we couldn’t use force, Captain Harris and I gritted our teeth and finished the statement as fast as we could.

We kept our voices steady, our questions focused. We got the confession on tape, signed the paperwork, and ended the interview as quickly as possible. When we left the room, I felt like I’d aged ten years.

The entire process was by the book.

Every form was signed, every tape logged. Harris double-checked everything, making sure there was no room for error. We knew this case would be scrutinized from every angle.

Afterward, we continued working through the night to ensure the documentation and evidence chain were flawless.

We drank stale coffee, eyes burning from lack of sleep. The paperwork piled up, but no one complained. We were determined to see this through, no matter how long it took.

Captain Harris even brought in our prosecutor colleague, Monica Evans, to review the case file—since after our investigation, the case would be handed over to the prosecution.

Monica arrived just after midnight, hair pulled back, eyes sharp behind her glasses. She read through the files. Asked a few pointed questions. Then nodded. "You did good work," she said. "This one’s airtight."

As long as these two stages were handled properly, there should be no problems with the case.

It was a relief to hear her say it. We all wanted to believe that justice would be served, that the system would work the way it was supposed to.

Prosecutor Evans agreed: this scum was doomed.