Chapter 1: A Childhood of Shadows

From the moment I was born, my mother was in my ear every single day.

Even as a baby, it felt like her voice seeped into every corner of our tiny apartment, always following me, filling up the air. Sometimes I wondered if even the apartment was tired of hearing her. I think I learned the sound of her disappointment before I learned any words at all.

"Quinn Delaney, you killed your uncle. You owe Hailey a life. You’ll spend your whole life making it up to Hailey."

She said it with a flat certainty, like it was gospel. She said it so often, it settled into my bones. Sometimes she’d mutter it when she thought I was asleep, sometimes she’d hiss it right in my ear while she braided my hair, her fingers tight and sharp.

To help me "atone," my mother secretly handed my aunt a $15,000 check as a kind of payoff or settlement when she remarried, all behind my dad’s back. After my aunt transferred custody of her only daughter, Hailey Chen, to my grandparents, she brought Hailey to our house. My mother made me, just eight or nine months old, kneel in front of Hailey and apologize.

It was the kind of thing that, if you told someone, they’d think you were making it up. I mean, what sense did it make? But there I was, a wobbly baby in a faded onesie, pushed to my knees on the threadbare carpet, my mother holding me upright by the shoulders, muttering apologies I couldn’t even form. The grown-ups all hovered, faces tight, watching me like I might somehow pay a debt I didn’t understand.

But I couldn’t even understand words at that age, and I especially liked to pinch people. Not long after three-year-old Hailey was brought in front of me, I pinched her little arm until it turned purple.

I was just a baby. No one ever told me not to pinch. And Hailey’s chubby arms were right there. I remember her shriek—sharp, startled—and the way everyone in the room froze for a split second before chaos broke loose.

Hailey cried out in pain, calling for her mom. My mother couldn’t comfort her, so she just kept smacking my tiny hand over and over.

The slaps were quick, stinging. My mother’s face twisted with something dark. I remember thinking she looked like a stranger. She hit my hand until it went numb, and the whole time, Hailey’s cries echoed through the house, high-pitched and wild. Even now, sometimes I swear I can hear them in my dreams.

"It’s not enough that you killed your uncle and torment me every day, now you even dare to pinch Hailey! You’re a curse, a child of sin, born just to bring me trouble. What good are you?"

Her words bounced off the walls, louder every time. I never knew what to do with the shame she pressed on me, not even old enough to walk.

Whenever Hailey was in pain, someone would comfort her. But when my hand hurt and I cried even harder, my mother ignored me. She even found my crying annoying, picked up Hailey, and left me alone at home.

The house would fall silent after they left, except for my own wailing. Sometimes the TV would be on in the background, cartoons blaring for no one. I’d crawl to the window and watch the dust motes spin in the sunlight, wishing someone would come back for me.

When my dad came home from his shift at the factory, I was lying on the floor, my face blue and unconscious.

He dropped his lunchbox right there in the doorway, keys clattering to the floor. I can only imagine the terror in his eyes—his baby sprawled on the linoleum, limp as a rag doll. He scooped me up, yelling my name, his voice cracking with panic.

My dad panicked and rushed me to the ER. The doctor said I’d fainted from holding my breath—nothing serious, just don’t let me cry too hard in the future. But my right thumb was broken. Even though they set the bone, my thumb might never straighten again.

I picture the fluorescent lights of the ER, the doctor’s tired face as he explained, my dad clutching my tiny hand. The cast was too big for my arm, my thumb a crooked little question mark for the rest of my life. My mother didn’t come to the hospital.

When my dad got home, he lost his temper, asking my mother how long she planned to torment us. My uncle’s death was an accident—his family was already ruined, did she have to break up our family too?

His voice, usually so steady, cracked like thunder that night. My mother just sat on the edge of the bed, arms folded, eyes hard as stone. The air in the apartment felt brittle, like one wrong move would shatter everything.

My mother didn’t argue. She just kept crying and repeating the same thing: "My brother was killed by Quinn Delaney. What’s wrong with making her pay for it?"

She rocked back and forth, clutching a dish towel, tears streaming down her cheeks. She said it like a mantra, as if repeating it enough times would make it true, would make her pain less sharp.

Seeing my mother was unreasonable, my dad filed for divorce and fought for my custody. My mother wouldn’t give in. She kept telling the judge that I broke my thumb myself, that she could never hit her own child, that no mother in the world didn’t love her child. After her explanation, and because she was breastfeeding, the judge finally awarded me to my mother, and my dad had to pay child support.

The courtroom was cold, the judge’s voice distant, almost bored. The courtroom smelled like old paper and coffee. My mother dabbed at her eyes with a tissue, playing the part of the wounded mother. My dad’s jaw was clenched so tight I thought his teeth might crack. In the end, the law sided with her—because I was small, because she was my mother, because the world expects mothers to love their children.

After the divorce, my dad was very upset and often tried to collect evidence of my mother’s abuse. Maybe my mother was wary, so she rarely hit me after that, and even if she did, she was very careful. Hailey got the bed. I slept on the floor. She bought Hailey new dresses, animal crackers, chocolate milk, and dolls, while I could only play with whatever Hailey didn’t want. If I so much as touched anything she hadn’t given up, Hailey would scream.

The floor was cold and hard, the smell of dust and old socks always in my nose. I’d watch Hailey twirl in her new dress, clutching a doll, while I curled up under a threadbare blanket, pretending not to care. I learned early to make myself small, invisible.

My mother would rush over and teach Hailey to hit my head. "Who told you to bully Hailey! Hailey, if she bullies you again, you hit her. If you hurt her, she won’t dare next time!"

She’d crouch down to Hailey’s level, her voice syrupy sweet, then turn to me, eyes flashing. It was like I was invisible. Hailey’s small fists would land on my head, and my mother would nod approvingly, as if she were teaching her daughter to ride a bike.

But Hailey was weak, and when she hit me, it didn’t make any noise like my mother’s slaps. So she felt it wasn’t enough and switched to twisting my arm and biting my hand. Every time, my mother would clap and cheer. "That’s right, doesn’t matter how, as long as it hurts her. Hailey, you’re great!"

Sometimes Hailey would look up, seeking my mother’s approval, and the two of them would share a smile. I learned to hide my hands behind my back, to flinch at sudden movements, to stay quiet so I wouldn’t make things worse.

When Hailey got tired of twisting me, my mother would get annoyed by my crying and lock me on the concrete back porch, starving me for a meal to "teach me a lesson."

The back porch was always cold, even in the summer. The paint was peeling, the boards warped. I’d huddle on an old mat, hunger gnawing at my belly, listening to the sounds of dinner drifting through the walls. The porch light flickered, casting strange shadows. I’d press my forehead to the glass, hoping someone would remember me.

Being beaten and bitten hurt, and being hungry was also hard to bear. I complained to my dad, who took me to confront my mother. My mother said, "Did I burn her with an iron or whip her? Is a slap abuse? What parent doesn’t lay a hand on their kid? Two kids fighting—she can’t beat Hailey, so it’s my abuse? If you don’t agree, go sue. See if the judge sides with you or me."

She stared him down. Daring him to try. He clenched his fists, knuckles white, but he didn’t say another word. I could feel the disappointment rolling off him, heavy as lead. The car ride back was silent, the air thick with things neither of us could say.

My dad was speechless, and that was the end of it. Because he didn’t see me often, my dad remarried within two years. We saw each other even less, and gradually grew apart.

His new wife, Aunt Melissa, had a polite smile and watchful eyes. They had two boys, my half-brothers, who grew up in a house where laughter was easy and dinner was always hot. I became a shadow, a voice on the phone once or twice a year.

I was taught to be obedient by my mother and Hailey. I no longer liked little dresses, animal crackers, chocolate milk, or dolls. All this I learned much later from my dad; I have no memory of it.

He told me, and it felt like someone else’s story. I couldn’t picture myself in pink frills or clutching a doll. My world was chores and silence, not playrooms and snacks.

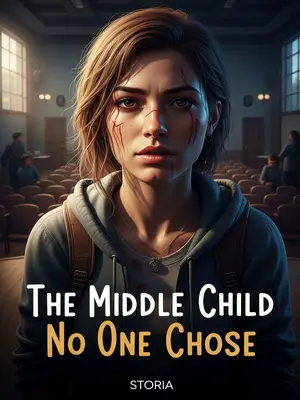

All I remember is that I never went to preschool, and at seven, I went straight into first grade. Not long after starting school, my classmates started calling me a weirdo because I never played with them or talked to them.

The other kids laughed and ran across the playground, their sneakers flashing in the sunlight. I wanted to join them, but I didn’t know how. I sat on the edge of the blacktop, tracing patterns in the dust, always on the outside looking in. Their voices sounded far away, like a radio in another room.

Actually, it wasn’t that I didn’t want to—I just didn’t dare, and I didn’t know how. Since I could remember, my mother made me atone to Hailey. She locked me at home to do laundry, cook, and mop the floor. I could only see outside through the window. No one ever taught me how to say "hi" to other kids. I only knew that every time I touched Hailey’s things, she’d tattle to my mother, and then I’d get hit on the head and locked on the porch to go hungry.

The world beyond the glass seemed bright and unreachable. My hands smelled like dish soap and bleach. The other kids’ laughter made my chest ache, but I didn’t know how to join them. I was always afraid that if I tried, I’d just get hurt again.

The teacher spoke to my mother twice about this. My mother, who sold pancakes out of a food truck in the Walmart parking lot, got angry at being disturbed and, without asking anything, hit my head in front of the teacher and twisted my ear to question me.

The teacher’s eyes went wide. My mother didn’t care. She yanked me by the ear, her voice sharp as a slap: "Why don’t you play with your classmates? Are you sick?" The whole class went quiet, staring. I wished I could disappear into the floor.

I had no answer. I also realized I was different from other kids. Maybe I really was sick.

I stared at my shoes, heat burning in my cheeks. The word "sick" clung to me, sticky and humiliating. I started to believe it. Maybe there really was something wrong with me.