Chapter 2: Small Town Scars

My mom was the town’s favorite subject for gossip, whispered over coffee at the diner and during the church bake sale. Her story was passed around like a cautionary tale.

She spent half her life supporting my dad, who never appreciated her, and nursed my grandfather for eight long years. She even helped my aunt and uncle get into good high schools. But in the end, all she got was my dad marrying someone else.

In our rural corner of America, marriage licenses weren’t always a priority. A big wedding reception, some cake, and a pastor’s blessing made you husband and wife. No paperwork needed, just community tradition.

My dad used that loophole to deny my mom was ever his real wife. He’d tell his new bride, "She’s just obsessed with me, always chasing me around." The new wife believed him, and soon everyone did.

He claimed my mom drugged him and had me to trap him, spinning wild stories at the local bar. He played the victim, nursing his beer as the regulars nodded along.

Back then, even basic cold medicine was hard to find. Folks relied on Vicks VapoRub, chicken soup, and a lot of prayers instead of pills.

My dad’s real skill was twisting the truth—he could flip any story and make the guilty look innocent, and the innocent guilty.

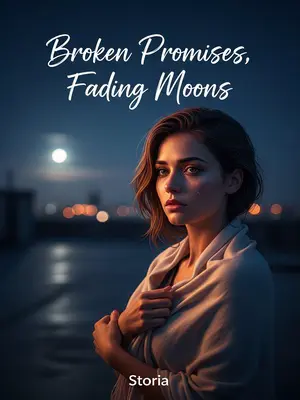

My mom was left alone, humiliated, and mocked by everyone.

She held my cheeks, her hands rough but gentle. "Emily, listen—never depend on a man. Don’t bet your future on anyone but yourself. Study hard, get out, and make your own life." I felt her callused fingers, the warmth and the weight of her words.

After she said that, my mom jumped off the bridge by the river. The wind was biting cold and the air smelled of water and mud. When they pulled her out, her body was so swollen I barely recognized her. The sheriff called me down to the bank, and I stood there, numb, my breath fogging in the early morning chill.

After my mom died, my grandmother called me a bastard and slammed the door in my face. My maternal grandparents, ashamed and convinced I was a Fields child, wouldn’t take me in either. I felt invisible—like a stray dog, no place to go.

At the time, our town was competing for a 'model American town' award. Sending a kid to foster care would be a black mark. The mayor was desperate to keep up appearances, so he scrambled to find a solution.

He arranged for me to get a subsistence allowance and applied for state subsidies. Whoever took me in would get a monthly check. It was all paperwork and signatures, but nobody really wanted me.

Mrs. Fields stepped up and took me in.

Trevor’s dad had died young, and his mom raised him alone. The Fields family owned a small patch of land, and their relatives were too poor to help. The farmhouse was drafty, and winters were brutal.

The mayor sent me to Mrs. Fields’s house, hoping two lonely souls could help each other.

Mrs. Fields always saved the biggest piece of pie for Trevor, bought him new jeans, and turned his old shirts into dresses for me. Still, I was never hungry or cold. I slept in the tiny room off the kitchen, wrapped in patched quilts that smelled of wood smoke and cinnamon.

I didn’t care about hand-me-downs; I buried myself in books, promising myself a better future.

One afternoon, the neighbor’s cows got loose and barreled toward me. I ran, heart pounding, as Mrs. Fields rushed out, yelling for help. She pushed me out of the way, but the cow clipped her leg. Neighbors shouted, and someone called the doctor.

She spent days in bed, barely conscious, clutching my hand with knuckles white as bone. Her breathing was shallow, and I watched her chest rise and fall, terrified she wouldn’t wake up.

"Emily, promise me—if I die, you’ll marry Trevor and take care of him." Her voice was weak, but the plea was desperate. I nodded, tears streaming down my cheeks, afraid she’d slip away. I whispered yes, my heart thudding in my ears.

The town doctor said it was just a surface wound and gave her a bottle of Vicks and some Tylenol. After a few days, she was up and fussing over Trevor again.

After that, Mrs. Fields told everyone I was her future daughter-in-law. At every church potluck, she’d beam and say, "Emily’s going to be family soon." She’d spoon out macaroni salad and deviled eggs, pride in every word.

After the county built a new highway, most girls left town and didn’t come back. Men joked at the diner that even at thirty, it was tough to find a wife. Someone would shake their head and say, "Shoulda tried Tinder, huh?"

Mrs. Fields always bragged, "I locked in my daughter-in-law before anyone else." She’d wave her coffee mug like she’d won the lottery, laughter echoing through the diner.