Chapter 2: Routine and Rupture

After graduating from university in 2005, I was posted to the correctional education department of a men’s prison nestled in the Western Ghats. My days were spent teaching psychological education to inmates, trying to correct their mental states so they could participate more fully in reform.

The prison itself was a relic from colonial days, its rusting gates and sun-faded yellow walls bearing silent witness to decades of regret and rage. During the monsoon, rain hammered the high compound walls, and sometimes peacocks called from the distant scrub, their cries echoing through the morning roll-call. Once in a while, you’d hear the bell of a chaiwala at the main gate, a small reminder of life beyond these walls.

Among the inmates was Arvind Yadav. He wasn’t a priority case. Sentenced to death with a two-year reprieve for intentional homicide, he’d already served more than a year. His behaviour was unremarkable—not especially active, but obedient, and never involved in conflict. He was quiet, almost blending into the background of the prison’s complex social order.

If he kept his head down for a few more months, Arvind would pass the reprieve assessment and likely have his sentence commuted to life imprisonment.

But fate had other plans.

Not long ago, Arvind erupted in a sudden, violent outburst—attacking his cellmate in a one-sided assault, each blow calculated to kill. In less than ten seconds, he beat the man to death. The guards barely had time to react.

Chaos swept through the barracks. Inmates screamed for help, some shrank back into corners, and even the most hardened wardens hesitated before entering. For a moment, Arvind seemed possessed by something beyond human.

A year of good behaviour had nearly made people forget Arvind’s past—a man who had killed and dismembered someone, a demon in disguise. Only his clever lawyer had managed to win him a reprieve.

Now, with another crime during his reprieve and under such grave circumstances, the death penalty became a certainty.

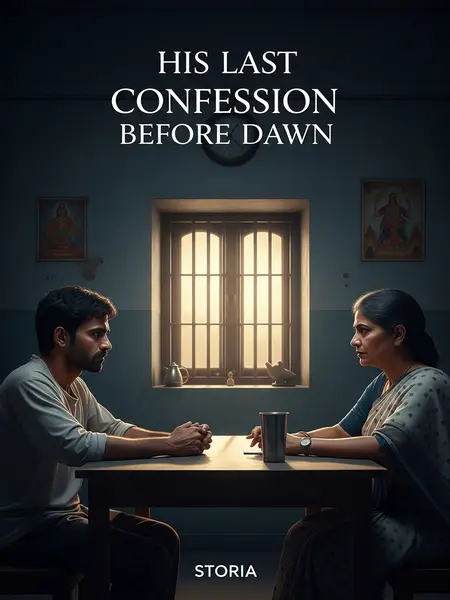

After the verdict, we notified Arvind a day in advance. He was told that every hour of his last day would be arranged—visiting relatives, bathing, a proper meal, psychological counselling, verification, and, finally, the execution.

There’s a certain irony in how the state’s slow machinery suddenly moves with such efficiency when a man’s end is near. The wardens turn almost deferential—slipping an extra sweet into the meal, permitting a longer cigarette, their voices subdued.

Arvind’s face betrayed a strange expression, but he said nothing.

I asked, "Kuch puchhna hai? Any questions?"

"Nahi," he replied—just one flat word, as heavy as the air itself. It felt like a door closing somewhere deep inside him.