Chapter 1: The Fall of the Nair Family

My father is a traitorous minister.

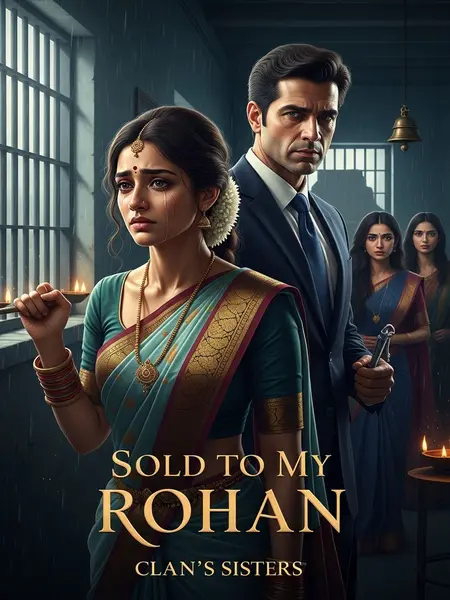

They called him desh drohi, splashed across the front page of the morning's English paper—right beneath a photo of my fiancé, Rohan, garlanded by the press, all smiles, as if my family’s ruin was a medal on his chest. Even my chachi’s voice trembled as she whispered, 'Log kya kahenge?' The one who seized our ancestral home in Girgaon, who now owns our silver, our mango orchard, and every last trunk of Kanjeevaram saris, is none other than my own betrothed, Rohan.

When he placed the iron chain around my neck—yes, the same hands that once crowned me with jasmine at our engagement in Bandra club—his hands were soft, almost reverent—like he was tying a rakhi, not a chain. Such double-facedness. That chain was colder than the December monsoon wind.

On the day my father was hanged and his body displayed at Rajpur Chowk, I calmly picked lice from my mother’s hair. The stench of sweat and old oil clung to us; the guards didn’t even bother to shoo away the flies. Amma sat with her saree pulled over her face, silent tears tracing lines through the dust. I said, “If there were a fire, I could fry these lice and have them with a glass of old rum.”

There was a beat of stunned silence from the women—grief momentarily halting even their breath. Then, Mausi managed a weak, watery laugh, the sound trembling and fragile, dark humour in the midst of sorrow.

Unexpectedly, this made the young army captain in the neighbouring cell, hanging by his collarbone, let out a short, half-choked laugh—a bark more than a laugh. Even in that dark place, irony could still bloom.

Is it really that funny?

All nine women of the Nair family were locked in the city jail, awaiting the Chief Minister’s verdict.

It was the jail behind the old collectorate—the one with blackened walls, a faded board that once read 'British Era Lock-up.' The musty air reeked of kerosene and stale roti. Somewhere in the corridor, a constable’s radio crackled out a film song, jarringly cheerful against our misery. Our fate would be to be auctioned like cattle in the old sabzi mandi or sent to the Government Women’s Home—the state-run brothel. Every woman in the city whispered horror stories: the light never went out, and even the walls remembered the cries. Some said the matron there kept a whip under her pillow, and that no girl ever left with her own name.

“Priya,” my mother called, her voice hoarse, “what time is it?”

Amma was unwell; the fever hadn’t left her since we were taken three days ago. She pressed her palm to her brow and closed her eyes as if praying. The green bangles on her wrist clinked—a tiny sound of home amid this nightmare.

I looked out through the small air hole at a patch of sky and whispered, “It’s around noon.”

“Noon…” My mother gripped my hand tightly, repeating the word helplessly, as if it could shield her. Noon was when the Nair family fell, when the clock stopped and the world outside forgot us. My father was about to be hanged, his name wiped clean from every register.

The men of the Nair family would be exiled to the border near Assam, the kind of banishment whispered about only in hushed tones. Amma wept bitterly, clutching her pallu, my aunts and cousins crying with her—the sound soft, like the murmur of pigeons in our old attic.

Mausi pleaded, “Priya, go and beg Rohan. Ask him to save you sisters, that’s enough—he can do it.” She clung to my dupatta, her face streaked with tears and kajal.

Rohan is my fiancé. Four years ago, he was a newly appointed IAS officer. My father admired his talent and arranged our engagement at the Cricket Club, all relatives in their best sarees. His career soared, and he became deeply trusted by the Chief Minister. But now, he is also the executioner who destroyed the Nair clan.

I wiped Mausi’s tears with the edge of my dupatta. “He won’t help us.” My voice was flat, but inside, something twisted—sharp and cold.

Mausi threw herself into my arms, sobbing. My cousins gathered around, crying, calling “Didi.” Their little hands clutched my kurta, as if I could shield them. I looked at the beam of light coming through the air hole. It was too high, too unreal—impossible to reach, like the city outside, now lost to us.

Heavy footsteps approached from behind. I turned, expecting the constable to announce the order. Instead, it was Rohan. He wore a deep maroon kurta, Nehru jacket, head held high, chest out, separated from me by a wooden rail. Our eyes met. For a moment, I forgot the dust and the flies. There was only the memory of coconut oil in his hair, the way he’d once laughed at my bad Hindi. A whiff of his musky perfume reached us, oddly out of place among the jail’s stench, and the click of his expensive watch marked his privilege.

At that moment, I remembered the first time I met Rohan. He wore a faded grey kurta-pajama, stepped forward, and folded his hands. “Namaste, Miss Priya.” Now, he holds high office, and I am a prisoner beneath his gaze. My throat closed.

Mausi pleaded with him to save the four of us sisters. She said their deaths were nothing, but we sisters, raised in comfort, how could we survive in the Government Women’s Home? She spoke in broken Hindi, her voice rising and falling like a prayer.

Rohan listened in silence, eyes fixed on me. I felt his gaze like a weight—cold, calculating.

He suddenly asked, “Why doesn’t the young lady beg?” The cell fell silent. My aunt’s hopeful gaze landed on my face. Amma’s red-rimmed eyes pleaded silently.

I understood what Mausi meant, and I knew Rohan’s intention. This was a test—a humiliation. I folded my hands and bent forward, touching my forehead to the dusty floor, the way my grandmother used to do in temple. “I beg Rohan Sir to lend a hand and save us sisters.” I bowed to him calmly, my voice steady. “If it succeeds, Priya is willing to repay you in this life, even if it means being a servant or a helper.” My hands pressed together in namaste, fingers trembling just a little.

Three feet apart, separated by a wooden rail, Rohan’s low, satisfied laughter echoed. He half-squatted, teasing, “All four sisters become my wives—would the young lady agree to that?” There was a sick humour in his tone, as if he relished my humiliation.

I paused for a moment, then continued to bow. I replied, “Sir is wise and accomplished. To be your wife would be a blessing for us sisters.” My face remained to the ground, but inside, I raged.

He laughed again. “I didn’t know the young lady could be so flexible.” His words cut, but I kept my head bowed, not answering.

“But it’s your blessing, yet my misfortune.” Rohan stood, brushed his sleeves aside, his cold voice falling on my head. “Young lady, I will come to the Women’s Home to see you.” The sound echoed, twisting my stomach.

Rohan finished, laughed loudly, and left. The slap of his chappals on the stone floor lingered.

I straightened, calmly watching his departing figure. “Priya.” Mausi hugged me, apologising, “It was foolish of me. I shouldn’t have let you beg that heartless man.” Her grip was weak, her voice broken. I comforted her, then turned my gaze to the cell next door, where a man hung by his collarbone.

A cockroach scuttled over my foot, but I didn’t flinch. There was nothing left to fear. His messy hair covered his face, sitting cross-legged in the corner, unmoving for three days. His silence was a strange comfort in this place of howling grief. I thought he was dead, but just now, I heard the sound of the iron chain on his collarbone. He was still alive.

As the echo of Rohan’s laughter faded, I promised myself—I would never beg him again. Not even to save my soul.