Chapter 4: Fire and Thunder

Inside those five years, Obinna dey find chance, dey meet people—some die for Adesuwa hand, but some escape, make name for themselves.

Through secret meetings under the old baobab, coded messages hidden in calabashes of palm wine, he built a network. Some fell—victims of betrayal or Adesuwa’s spies. Others survived, carving their own legends in backroom whispers and midnight songs.

Five years waka pass like play.

The passage of time was marked by new cracks in the palace walls, new faces among the guards, old hopes worn smooth by disappointment. Obinna’s hair grew greyer at the temples, but his eyes never lost their fire.

Japanese people, after the Calabar coup, invade Bakassi, their navy rush enter Atlantic coast. Plenty Igbo people die for Japanese bullet. Obinna dey read battle report over and over, him eyes dey burn—but him hand tied.

He pored over the torn pages of the reports, fingers trembling with rage. The ink smeared, the words blurry from too many rereads, but the pain was always fresh. Each casualty number was a scar he wore in silence.

These Japanese no different from the British wey burn Royal Library; once dem no get supply, na to loot Igbo towns, bayonet dey pierce anybody wey stand, the oyibo and yellow skin soldiers dey laugh inside fire.

The stories filtered in from traders and fishermen—children hiding in yam barns, mothers clutching their babies, bullets flying like swarms of angry bees. The laughter of the invaders was a sound he would never forget, ringing louder than any battle drum.

For their eye, Igbo and Garba na the same—no be human.

The invaders saw only targets, not people. Obinna felt their contempt seep into the soil, poisoning even the rain that fell on broken roofs.

Once dem kill one, no need to pity the family. Anywhere the big powers pass, na only naked women, children with belle cut open. Those pikin, just now dey call their papa and mama, next thing, bayonet don run through their belle.

Obinna’s stomach knotted at the stories—the slaughtered children, the wailing mothers, the echo of pain that refused to fade. He remembered their faces at night, their cries gnawing at his resolve.

As belle burst, pikin dey cry, still dey look for who go carry am.

But nobody go carry am again—the parents self don die. As the pikin dey see their parents face wey dey pain, dem fear, cry louder.

He felt each orphan’s cry as a wound in his own heart. The sound, he imagined, must rise to heaven itself, demanding justice that never came.

But the cry no dey last. Dem go cry till voice finish, the sound go lost inside laughter—those white and yellow skin soldiers dey laugh, knife full of blood, pikin corpse dey hang from the blade.

Obinna could almost hear the cruel laughter, see the bloodied bayonets glint in the sun. He gripped the edge of his chair, knuckles white, as the ghosts of the murdered pressed in.

These things na from the notes of our own people, from reports of those war journalists wey still get conscience, reach Obinna table.

He cherished those reports, fragile as old love letters, knowing that truth was all that remained when hope was gone. Each line was a funeral drum, each page a burial shroud.

Obinna close eye, say, "Make all these things reach the Old Mother…"

Halfway, Obinna stop, because he sabi say Adesuwa no go look, she no even want hear. Few days back, person tell her make she use birthday money fight Japanese, Adesuwa vex:

The memory returned: Adesuwa’s eyes flaring, her lips curled in contempt. ‘Who dey talk that nonsense for my palace? Make I no see you for my party! Birthday na for enjoyment, not for war!’ The whole palace felt the chill that day, as if harmattan itself had entered the room.

Adesuwa talk say, "Anybody wey spoil my mood today, I go make sure dem no get peace for life."

The threat hung in the air, as heavy as the scent of burning palm oil. Even the boldest chiefs tiptoed around her, voices low, faces blank.

With her sixtieth birthday near, no single bad news fit enter Adesuwa ear.

The whole palace became a theater—everyone smiling, even when their hearts bled. Laughter echoed off marble walls, but sorrow crouched in the corners, waiting for night.

These days, Adesuwa na only enjoyment she dey find, na only make Obinna kneel for her front, call her dear father, kneel for Palm Grove Estate, kneel for Big Market Road, kneel for Royal Compound.

Obinna’s world shrank to a ritual of forced bows and brittle smiles, the taste of shame sharp on his tongue. The servants learned to anticipate the kneeling, spreading fresh mats and dusting the floors so his suffering would be spotless and seen by all.

After one full day of kneeling, Obinna slump for table, night don cover everywhere. He look down at the notes and reports, the words too real, like say the dead pikin and destroyed city dey before am.

The candle flickered, casting twisted shadows on the walls. Obinna’s shoulders sagged; his hands shook as he read and reread the lists of the dead. The ghosts of the fallen seemed to fill the room, crowding out hope.

All the anger wey he don hold for five years, all the negotiation and patience, everything just scatter.

The dam burst. A single tear slipped down his cheek, tracing the path of old scars. He slammed his fist on the table, the sound echoing like thunder. ‘Enough is enough,’ he whispered, voice raw. His hands shook, sweat cold for his back, but his eyes dey shine like torch for dark night.

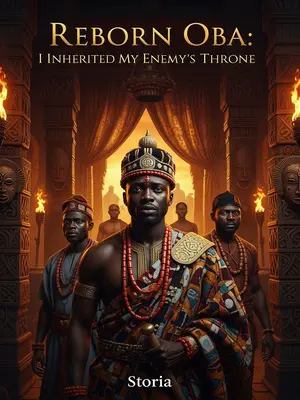

Second day of the tenth month, twentieth year of Adesuwa’s reign, stars and moon high, cold harmattan wind dey blow, Obinna suddenly lift head from table.

The night air crept in, sharp as knives. The room glowed silver in the moonlight, and Obinna felt a surge of courage rise in his chest. The time for talk had passed; the time for action had come.

He tell the palace attendant near am, "Sule, go tell Musa Okeke, I no dey do talk again. Tonight we go act—whether he come or not, if I no move now, I no be Son of the Soil, I no be the leader of all people."

His voice thundered through the quiet. Sule froze, eyes wide, the weight of history pressing down on both of them. Obinna stared him down, a general awakening beneath the king’s mask.

The attendant just dey shake, say, "Your Majesty, Musa Okeke own mind no clear…"

Sule’s knees knocked together, voice barely more than a croak. The scent of fear drifted between them, thick as the evening incense from the palace shrine.

"Matter for this world no get time for delay. Wetin I dey do, na for the people. I be Mandate of God—where private wahala dey come from?"

Obinna’s voice was deep, every word landing like a royal edict. ‘If I perish, I perish. But I go stand for my people till the end.’

The attendant begin shake for body, eyes red, kneel down, wan bow, but Obinna drag am up, talk with heavy voice, "Go."

Obinna gripped Sule’s arm, lifting him with the strength of a man who had carried too much for too long. The command was final—no more delays, no more fear.

Tears just rush come out for attendant eye. He turn, waka leave the big, deep palace.

Sule stumbled away, tears shining in the moonlight, his footsteps echoing down the marble hall. For the first time in five years, even the palace walls dey shake small—like say everybody dey wait for thunder to strike.

Five years—Obinna look inside the thick darkness: How I take live these five years? How many people I don meet, how many secret order I don give, how many people I don try win over…

He let the memories wash over him—the faces of friends lost, the whispered promises, the silent prayers. Each one was a link in a chain he could no longer carry. The darkness pressed in, but Obinna’s resolve burned brighter.

After tonight, I no go kneel for anybody again.

His heart thundered in his chest, the old fire roaring back. ‘By this time tomorrow, the world go know say Lion nor dey bow for goat.’

After tonight, proud Umuola—how you go allow clowns dey run anyhow!

He stood, shoulders squared, ready to reclaim his place in the saga of his people. The moon watched as witness, the wind carried his vow. Umuola would rise or fall, but Obinna would never kneel again. By this time tomorrow, the whole kingdom go sabi say true lion nor dey fear thunder.