Chapter 3: Adjustment, Birthdays, and Friendship

Saturday. I was dreaming of jalebis at home—no rent, no deadlines. Then—BANG!—reality hit like a Mumbai local.

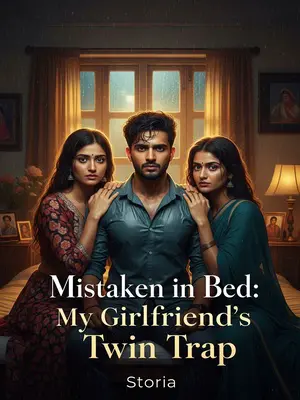

The bedroom door burst open. Meera’s face, flustered and breathless, filled the doorway.

"Didi, next time can you knock first?" My voice was squeaky. Still half-dreaming, I pulled the bedsheet up to my chin.

"I did knock." She pointed at the new dent in the wall. I couldn’t help but laugh.

"Even a thief wouldn’t knock that hard."

‘Only Meera can turn a knock into a home invasion,’ I thought, but kept it to myself.

"Why don’t you lock your door?"

"Look at this busted door—does it look like it has a lock?" I pointed at the hole where the lock used to be. Useless, like my old school report cards.

She waved her hand. "It’s fine. I just came to borrow a couple of hangers. Forgot to buy some after doing laundry."

Her casual air, like she owned the place, made me sigh. ‘At least ask, yaar,’ I thought.

"Take them yourself." I curled under the covers. "I’m not exactly dressed right now."

I peeked under the blanket to check my Chhota Bheem boxers. Some things are better left unseen.

She smirked, then straightened her face. "What, busy with your hands?"

I nearly fell off the bed. Only in India would someone throw that line and then act like nothing happened. My ears went red, and I buried my face in the pillow, mumbling about ‘privacy’.

"Oh, Chhota Bheem boxers." She took the hangers, corners of her mouth twitching.

"Come on, didi, say something new. Want me to lend you a pair?"

I tried to sound cool, but it came out wrong. Her footsteps retreated faster than Virat Kohli running between wickets. I grinned and relaxed.

Roommates, right? There’s always an adjustment period. Every Indian who’s ever shared a flat knows—there will be war. Over milk, AC, mopping. My parents call it ‘adjustment’. I call it ‘daily battle’.

I thought adjustment meant learning boundaries—like the India-Pakistan border. Don’t cross it, and you’re a good roommate.

She wasn’t like that. She knew your boundaries—and then kept dancing over the line. It was like she was doing Bharatnatyam on the border, one toe in, one toe out, all with a smile.

Like barging into my room without warning, treating the place like her ancestral haveli. Or using the bathroom while I was brushing my teeth—she’d stumble in, half-asleep, pyjama down, and sit on the toilet. Indian privacy is already stretched thin, but this was next level. I’d be brushing away, thinking about deadlines, and suddenly—‘Arrey, bhai!’

Her scream was so loud, even the crows took flight. Still, she never learned. Sometimes I thought about putting up a sign: ‘Occupied! Respect privacy!’ But what’s the point?

She was hopeless at life skills. She could recite Taylor Swift lyrics, but didn’t know how to make chai. Once, she asked why her laundry never got clean—turns out, she hadn’t added detergent. Her face was so innocent, like a kid just told Santa isn’t real. I laughed, then showed her how to pour Surf Excel without losing half to the floor.

She insisted on cooking, even though she couldn’t. Nearly burned the place down. First time, the kadhai nearly melted. Flames shot up, and I had to use the fire extinguisher my mom forced me to buy. Saved the day, but the kitchen still smells of burnt halwa.

At least she learned fast. One YouTube tutorial, and she was rolling round rotis. Second time, she knew not to throw water on an oil fire—used dish soap instead. The kitchen turned into a bubble bath, but hey, at least there were no flames!

July 16th—her birthday. In our house, birthdays mean laddoos and blessings. Here, it was just another rainy Mumbai morning, except for Meera’s constant mumbling.

She kept muttering in the living room: "Today’s my birthday, please don’t make me work overtime." Her eyes darted to her phone, hoping her boss would say, ‘Meera, take the day off, yaar.’

I tried to stuff the pillow over my head, but her voice pierced through like a temple bell at 5 am. By the time I got up to scold her, she’d already left. Her perfume lingered, mixed with yesterday’s fried onions.

She left in a hurry—her bedroom door wide open. I peeked in, just a little. Not the snooping type, but curiosity won. Swiggy boxes on her desk. So many empty boxes! My heart went out to her. No one deserves to eat alone on their birthday. Half a samosa, half a bowl of poha, two boxes of sabzi. No cake, no candles—just leftovers and cold chai.

On a whim, I went downstairs to the kirana. Uncle threw in extra green chillies. I bought paneer, potatoes, even a tiny cake from the bakery.

Timed it so I’d be cooking when she got back. As onions and tomatoes sizzled, the flat filled with smells of home. Even the neighbours peeked in to ask what the celebration was.

When she walked in, umbrella dripping, eyes half-closed, she saw the food. Four dishes, dal, and a tiny cake on the table. Steel plates, paper napkins, a single candle.

She looked stunned. "What, you have friends coming over tonight?"

I took off my apron. "Nope, just celebrating a silly girl’s birthday."

Her eyes welled up, but she blinked the tears away. Meera never liked showing weakness. I quietly slid the plate of paneer towards her, saying, "Maa ke haath ka nahi hai, par chalega na?"

She grinned, wiping her nose on her sleeve. Happiness infectious. I put on a straight face. "Didi, honestly, if you’d been any louder this morning, the whole building would know."

She burst out laughing, finally relaxing. I felt a strange warmth inside—like I’d finally done something right.

"Just happened to buy some Old Monk. Let’s have a drink."

She waved the bottle, eyes shining. I could only laugh. "I can’t really hold my liquor. Let’s take it easy."

Six beers, three each. It was like drinking cold water, but the mood was good, and the food better. I went down for six more. The bhajiwala gave me a knowing look: ‘Arrey, party chal rahi hai, kya?’ I just grinned.

I looked at her. "Didi, just tell me—how much can you actually drink?" She arched an eyebrow at me, and I grinned back, feeling like we were in our own little World Cup final.

She got shy, holding up one pinky finger. I laughed so hard I nearly dropped my glass. "You sure? Only one more?" She nodded, lips pursed in mock seriousness. "Keep going."

Men—especially North Indian guys—hate being outdrunk by a woman. I’d claimed I couldn’t drink so she wouldn’t feel pressured, but tonight, it was one standing, one lying down. Stakes set, I made up my mind—not to lose face.

I went down again, lugged up two crates—twenty-four bottles each. The watchman just shook his head and laughed.

After eating and drinking, we lit candles, made a wish, ate cake, and burped a few times. Even the burps felt like a victory. For a while, the flat didn’t feel so lonely.

Somehow, we felt closer. It was a quiet closeness—like siblings fighting over the last gulab jamun. Warm and real.

"You know, you’re not much to look at, but you’ve got a good heart. Since my dad died, this is the first time anyone’s celebrated my birthday."

Her words hit me in the chest. I just nodded and offered another slice of cake.

Sometimes, words aren’t needed—my dadi used to say. This was one of those times.

"You, silly girl, pretty and with a nice figure, but why did you have to grow such a sharp tongue?"

She grinned, swatting my arm. For a moment, it felt like home.

With a bit of liquid courage, I finally asked what I’d been wondering. "Judging by your looks, you must’ve grown up well-off. Why are you renting here?"

She didn’t get angry—just looked away, twisting her dupatta. "My family used to be rich, but my dad got sick. We spent everything trying to cure him, but it wasn’t enough. He passed away three months ago, so I came out to work."

Just a short sentence, but it carried all the bitterness in the world. Life is tough. I poured us both another drink and let the silence do its job.

I wasn’t insensitive enough to ask about her mum. In India, you learn young: there are questions you don’t ask unless the other person brings them up first.

That night, she didn’t go back to her room. She just fell asleep on my thigh.

Her head was warm and heavy, her breath slow. My leg tingled, but I didn’t move. Outside, rain lashed against the windows, as if the city was crying with her. I sat there, listening to the rain and the distant traffic, feeling protective in a way I hadn’t felt since childhood.

She mumbled in her sleep—snatches of ‘Papa’ and something about ‘home’. I just sat there, not daring to wake her.

Maybe she was dreaming of her dad. Maybe she thought I was her dad. Whatever it was, I hoped she found some peace. Mumbai can be a lonely place, especially after loss.

As for me, I didn’t sleep—not because I was thinking anything funny, but because my leg went numb. Next morning, I hobbled around like an old uncle at the park, but it was worth it.

After that, we became friends. Ordinary friends—the kind who eat snacks and watch TV together. We’d argue over what to order or whose turn it was to buy milk. There was comfort in the routine—like family, but not quite.

She probably liked my personality. I mostly appreciated her beauty. I sometimes wondered what the neighbours thought—boy and girl, living together, always laughing. But in Mumbai, everyone minds their own business.

One day, just another weekday. Rain outside, sweat trickling down my back. She was showering, I was in the living room, eating, watching daily soaps. WhatsApp pinged during an awkward silence. Neighbour aunty’s footsteps echoed in the corridor, and somewhere, a temple bell rang faintly through the rain.

Between us, only that broken, unlockable door. As usual, I’d propped a chair against it, half for privacy, half because the wind sometimes made it creak open.

Arrey—

Suddenly, a shriek split the air. My spoon dropped, dal splattering my shorts. Before I could react, Meera burst out—wild-eyed, panicked, and…

A scream. She rushed out in a panic. Her voice so loud, even the pressure cooker next door seemed to whistle in reply. I leapt to my feet.

She was completely naked.

The world seemed to stop. My mind went blank, except for one word: ‘Bas, ho gaya.’

Honestly, I was stunned. I froze for three seconds. I stared so hard at the TV, I could’ve recited Tulsi Virani’s monologue by heart. My ears burned, and I prayed to all thirty-three crore gods to erase the last three seconds. My hands shook, and I covered my eyes, peeking through my fingers like a kid at a horror movie.

In those three seconds, a lifetime of sanskar and embarrassment flashed by. I wanted to look, but didn’t dare. I fixed my gaze on the TV, pretending to be deeply interested in the latest family drama.

Looking felt wrong. Not looking felt like I was missing something important. My head spun with confusion. I could almost hear my mother’s voice—‘Beta, behave!’

All I could do was stammer, "Arrey, kya ho raha hai yaar?"

"The geyser... electric shock..."

Her hands trembled, eyes pleading. I nodded, trying to look sympathetic but really just wanting the ground to swallow me up.

"Whatever’s shocking you, can you please go put some clothes on first?"

I managed a weak smile, not quite meeting her eye. She darted back into the bathroom, slamming the door. Only then did I let out my breath, muttering, ‘Ye toh gaya kaam se.’ Even in Mumbai, some things are just too much for one day.

The next morning, neither of us mentioned what happened. But the bathroom door got a brand new lock.