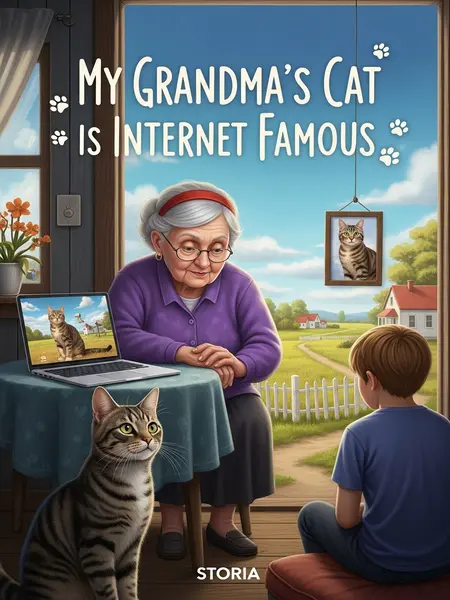

Chapter 2: Country Life with Grandma

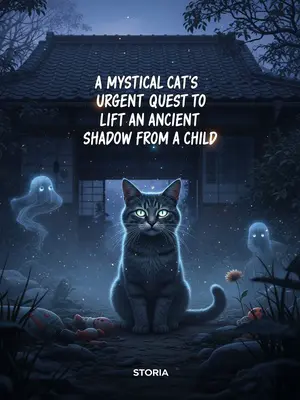

I am a cat.

I live in the country with Grandma.

A week ago, Grandma’s little grandson found me—just a tiny scrap of a kitten—and brought me home.

He gave me a bath, fed me hot dogs, and cuddled me to sleep.

Back then, I had a pretty silly name: Whiskers.

But Grandma’s son didn’t like me. He said having a cat in the city was too much trouble, and that kittens carried all sorts of germs and fleas.

So, he bundled me up and sent me off to the country.

Parting was hard.

The little grandson sobbed and clung to Grandma’s sleeve, wailing, “Grandma, her name is Whiskers. You have to take good care of her!”

“Dad says I can come see Whiskers when school’s out this summer!”

Grandma looked confused. “Uber? What’s an Uber? Is that like a new kind of lawnmower?”

“Big guy, be good, don’t call an Uber—that’s just wasting money.”

Grandma’s hearing isn’t the best.

When others say ‘front porch,’ she hears ‘lunch torch.’

The little grandson bawled even louder. “Not Uber! Whiskers! Whiskers! Whiskers is the kitten!”

Grandma’s face changed. She patted his sleeve and promised, “Eat barbecue together? Sure, next time you visit, Grandma will buy you barbecue.”

The little grandson was devastated, crying, “Help! Grandma’s gone deaf!”

Grandma slapped the table. “Want brownies again? No problem!”

Not only is Grandma hard of hearing, she’s got a knack for rhyming.

She hurried to comfort him, stuffing his pockets with candy bars. The wrappers crinkled as she tucked them into his jacket—Snickers, Reese’s, even a squashed granola bar she found at the bottom of her purse. "There you go, sweetie, some road trip snacks for you and your dad."

Even as he was carried off by the scruff of his neck and put in the car, he was still shouting, “Whiskers!”

Once the commotion died down, the yard fell silent.

The porch creaked under Grandma’s weight, and the smell of cut grass and diesel from the neighbor’s tractor drifted over the fence. Grandma and I sat on the porch, staring at each other.

She glared at me and said, “Listen up, I’m not taking care of you. It’s hard enough for this old lady to feed herself, let alone look after a little rascal like you.”

Her words made me anxious.

I didn’t dare follow her inside. I just sat frozen on the porch.

There are a few chickens in Grandma’s yard, and a maple tree.

The chickens clucked, and the shadow of the maple tree stretched long and dark. A rusty wind chime tapped quietly overhead, mixing with the afternoon hum of cicadas.

Grandma was shelling beans under the awning. Her hands shook so much, a few beans slipped between her fingers and rolled into the grass. I trotted after them, feeling like her little four-legged helper.

Beans rolled all over the yard. Grandma sighed, “What a waste. Gotta pick them up, gotta pick them up.”

Grandma’s legs aren’t good—she walks slow, nowhere near as quick as my four paws. So, I helped her chase down the beans.

Whenever I found one, I picked it up in my mouth and brought it back, dropping it into her palm.

Grandma and I stared at each other again.

She kept up her tough act: “Don’t think picking up a few beans means I have to keep you. I mean what I say—You’re not getting any supper tonight, you little troublemaker.”

After shelling the beans, she muttered about going out to buy fish.

So, I followed her.

She rode her old bike, and I trotted along behind, chasing her wheels on my little legs.

The country road was rough. My paws got muddy—and I even stepped in cow manure.

I couldn’t stand it.

The ground felt like it was zapping me, and with every step I had to shake my paws clean. Every few feet, I’d stop and flick my toes, little brown flecks flying off onto the gravel.

Grandma’s bike had a faded Cubs sticker on the fender, and the local diner’s neon sign buzzed in the distance. The bike wheels rolled into town, and soon Grandma was arguing with someone.

“Don’t you care if your dog pees everywhere? I clean my bike wheels every day, and the moment I go to buy fish, your dog pees on them!”

The man played dumb, pretending not to hear, tugging his dog and trying to leave.

Grandma grabbed his arm. “Can’t you hear me talking to you? Clean it up before you go!”

He shook her off, pointed at her nose, and snapped, “Lady, are you serious? My pit bull’s worth more than your old Schwinn.”

“So what if my dog peed? Do you know what breed this is? Open your eyes—this is a pit bull!”

The man’s voice boomed, and his dumb dog barked just as fiercely—man and dog, both acting tough.

“My dog’s worth more than your bike. If it peed on your wheels, you should feel honored.”