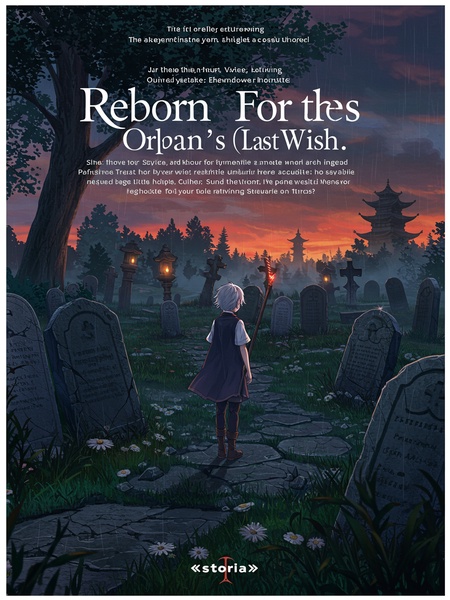

Chapter 2: The Weight of Memory

I don’t even remember how long I’ve been dead.

Some nights, the silence is so thick, I imagine my own memories crumbling away, grain by grain. Only my name—Lakshmi—remains, everything else faded like an old photo left out in the monsoon.

My past grows fainter every day. All I remember is my name: Lakshmi. Nothing more.

Funny, isn’t it? In life, everyone worries about legacy—what will people say, what will my children remember? But in death, all that’s left is a name, floating in me like a diya flickering in the wind.

I lay on my grave, soaking in the moonlight.

The moon’s glow was soft, pale like the milk boiled for prasad on Shivratri. The marble slab cooled my back, and I listened to stray dogs barking and the distant beat of a wedding band somewhere in the galli.

Yamdoot appeared quietly beside me, lying down as if this was a regular Friday night.

He always appeared without a fuss—no ghungroo, no dust, just a chill and the faint smell of camphor. Sometimes, I wondered if he was bored of his own work. That night, he lay beside me, arms behind his head, like a nephew pestering his mami.

“Aunty, have you decided which family you want to be born into next?”

His voice was teasing, almost playful. If you didn’t know better, you’d think he was just a nosy relative.

When I didn’t answer, Yamdoot got anxious. “Your time’s come for reincarnation, you know. If you delay, it’ll be bad for you and for others. I’ve got so many good families here, why not just pick one?”

He took out a scroll, listing names like a rishta-wali aunty at a marriage bureau. “There’s the Mehtas in Andheri—nice bungalow. Or the Pillais in Chennai—good people. Just say which one!”

Yamdoot said I’d earned great punya, and after death, people built a mandir for me. I got prayers and diyas from all over.

He puffed up his chest, as if he deserved credit for my afterlife comforts. “Not everyone gets a mandir, haan. Your devotees come from far, lighting diyas and tying red threads on the neem tree, asking for your blessings.”

So I could choose my next parents.

It was a privilege, I guess. Others might have jumped at the chance. But I just felt tired.

I rolled over, turning my back to Yamdoot.

My dupatta slipped, catching a patch of moonlight. I tucked it back, not caring if he saw my indifference. Let him wait. Let everyone wait.

No matter how much he tried, I never replied.

He huffed and puffed, but I just ignored him. Sometimes, silence is the only protest left.

There must have been something weighing on my heart, making me unwilling to reincarnate.

I gazed at the stars, searching for answers. In our stories, the dead always have some unfinished business, na? I suppose I was no different. A heavy stone sat in my chest.

Yamdoot left, grumbling. As soon as he vanished, the little girl who mistook me for her Ma arrived.

He disappeared in a swirl of dark smoke, muttering about stubborn souls. Within minutes, the air shifted. The girl’s slippers slapped the mud, her presence as stubborn as the monsoon.

Three months ago, a group came to my grave.

They wore crisp khadi kurtas, muttering mantras. The men dug with tired arms, shoveling red earth while women stood with folded hands, eyes dry but resigned. The priest kept glancing at the shadows.

They placed an empty coffin atop my own.

The wood was fresh, pale, reeking of varnish and loss. The thud was hollow—a secret meant to be hidden.

Since then, a girl of twelve or thirteen started coming every few days.

She’d arrive in the morning, hair in rough plaits, face smudged with dust and sleep. Sometimes, in the orange evening light, as the city quieted. She never missed a visit, not even when the rains turned the ground to slush.

She called my grave ‘Ma’, laying out her offerings—sometimes a steel dabba of biryani, sometimes a string of jasmine flowers.

Once, she brought coconut laddoos wrapped in newspaper. Another time, a faded photo—her Ma in a crisp green saree, saluting with pride.

She would mutter little lies.

Her voice always trembled, as if the truth might escape if she wasn’t careful. She lied to herself as much as to the grave.

She’d say, “Ma, your daughter is living well at home, don’t worry about me.”

But even the birds knew better. Her voice would crack, and she’d blink away tears that wouldn’t fall.

But she was clearly not well. On her thin wrist were many bruises.

The marks mapped her suffering—old and new. No amount of talcum or long sleeves could hide them from someone who knew pain.

It was obvious she had been mistreated. How could she be well?

Even the ants crawling over the sweets seemed to sense her misery. The graveyard’s silence only made it more obvious.

She also asked, “Ma, are you cold down there? Do you have enough to eat?”

Her words were barely a whisper, trembling with concern. Sometimes she’d tuck her dupatta end along the grave’s edge, as if to keep me warm.

I thought, little girl, you should worry about yourself.

If only I could say, ‘Beta, eat first, sleep well—your Ma wants you safe and happy.’ But my words hung unsaid, as the world spun on uncaring.

In the chilly spring, she wore only thin clothes, her hands red with cold, her face pale as death.

Her chappals were cracked, toes peeking out, and the wind made her shiver. Still, she never complained. The world had taught her not to expect kindness.

She was so frail a gust of wind might blow her away. If her Ma were truly here, she’d be heartbroken to see her child like this.

I pictured her Ma’s spirit weeping helplessly. A pain only mothers know.

Thinking this, I became inexplicably irritated, my heart felt blocked up.

A lump formed in my throat, heavy and immovable. Even in death, I felt anger—a strange, bitter comfort.

Something wanted to break out of my mind, but no matter how I tried, it wouldn’t come.

A memory clawed at the edge of my mind, desperate to be free, but I held it back—some truths were too raw to face just yet.

I floated above the grave, basking in sunlight, enjoying her offerings.

The sunlight was warm on my ghostly skin. The poha, the biryani—each bite was full of longing and love, seasoned with a daughter’s hope. Even spirits have their small joys.

Unlike other spirits, I could appear in daylight and show myself to the living.

People say bhoots only roam at night, but I, Lakshmi, was different. Sunlight gave me strength. Maybe it was the prayers, or my old life as a protector.

After eating and drinking my fill, the little girl would reluctantly look at my grave and hoarsely say goodbye.

She’d pack up, wrap the empty tiffin, tuck her hair behind her ear, and give one last look to the stone.

“Ma… be well down there. I’ll come again. If there’s anything you want, just appear in my dreams—I’ll bring it next time…”

The promise floated in the air, half-prayer, half-bargain. The kind of thing children say to keep hope alive.

As she spoke, her eyes turned red, she sniffed hard, and whispered, “Ma, I miss you, come see me in my dreams…”

Her lips quivered, and she pressed her face into her dupatta, muffling her sobs. Even the crows fell silent at her grief.

Seeing her tearful eyes, my heart ached with every beat.

Some wounds only the heart feels, and in that moment, I remembered what it meant to be human. Old pain washed over me.

It felt like I’d seen this scene before.

A half-remembered memory tugged at me—another child, another grave, another lifetime ago. The cycle of longing never ends.

I couldn’t help but call out as she turned to leave.

The words slipped out before I could stop them. Even the dead can feel helpless before such sorrow.

“Don’t go.”

Continue the story in our mobile app.

Seamless progress sync · Free reading · Offline chapters