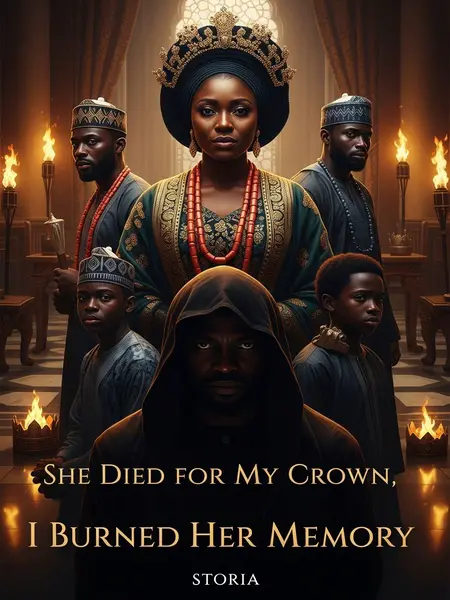

Chapter 1: Ashes of Loyalty

My only friend na woman wey cross come this world. She always said, ‘Na only you carry me come this world, Fola. I no fit leave you.’

Something dey for the way she go look me straight for eye—stubborn like old palm wine wey don turn—and talk am without shaking. For this wide, sharp-edged world wey everybody dey mind their own, Ifeoma carry my matter for head like basket of orange. You go see am for the small small things she do—the way her voice go soft when she dey talk to me, or how she always stand between me and wahala, even when wahala wear agbada hold staff of office.

She believe in me, protect me, even give everything wey she get make my husband wear crown.

Some people dey talk loyalty, but Ifeoma dey show am with hand. She give her savings, her prayers, her midnight vigil, her laughter, even the beads for her wrist just so Musa Danjuma fit wear crown. For palace, people dey whisper, but na only me know the fire wey she carry for me—she be the lamp wey refuse to quench when wind dey howl.

Last last, she see person wey truly love am.

Ifeoma own joy, after many storms, be like harmattan rain—rare, unexpected, but real. E be like say fate finally remember am. The way she dey smile, eye dey dance, when person finally hold her heart gentle. Na that kain happiness make people talk, “E go better.”

She talk say this place dey warm her, and say she wan stay for this world.

She go touch her chest say, “The sun for here dey different.” She fit complain of dust and mosquito, but na children laughter, mama‑put jollof smell, and the soft hum of evening prayers make am decide. “Na this world,” she talk, “my soul fit breathe at last.”

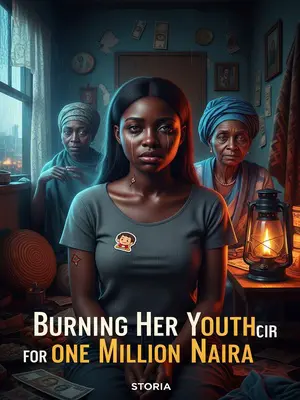

But later that night, I rush back from border, ride through the night for one battered okada.

That night, the sky itself was weeping. I sped down the red earth road, heart pounding like bata drum. The old okada rattled beneath me, every pothole jarring my bones, but I did not care. The air stung my face, thick with the smell of roasted corn and burning firewood. All I could think of was Ifeoma, calling my name in the wind.

Yet all I found was her pale, thin body lying alone in the white casket, cold as harmattan stone.

When I entered the room, everything went silent – even the flies froze in the air. Ifeoma’s skin was so pale, as if the last colour had drained away with her laughter. The white casket looked too big for her, as if it could swallow her whole. I touched her fingers. Cold, stiff. My heart squeezed.

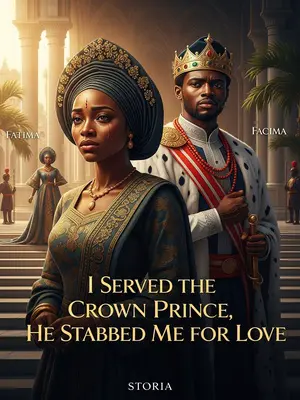

Beside the casket, her husband stand like person wey lost road, speechless.

He looked empty, like a broken calabash. His lips trembled, but no words came. Even the mighty Musa Danjuma, the lion of the council, was brought low by the finality of death.

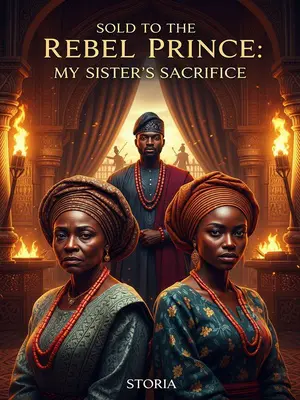

The boy discomfort don dey build since morning—him leg dey shuffle, him eyes dey dodge everybody for front mourners. Earlier that week, when Ifeoma scream tear her hair for front him classmates, shame burn him face. Now the small pikin whisper with relief, "Thank God o, I no want that kain mad woman as mama."

The words cut the air pass razor. The boy eyes, wey dey shine before, flicker with relief like say dem just drop heavy load from him shoulder. The women for room exchange glance, some nod small for silence. My blood just dey boil.

I look the woman wey stand near father and pikin, dey pretend cry.

Her sobs too loud, too perfect. She dey dab her eye with a white lace handkerchief, but her gaze dry, dey waka about to see who dey look. My spirit recoil from her like bitter leaf.

I tell myself say I no need pretend again.

Inside me, something snapped. All these years, I had played the role expected of me—dignified, measured, a proper queen mother. But now? For Ifeoma, all that pretense scattered like pap in hot water. Let them see my true face.

After today, dem go see wetin real madwoman be.

Let them tremble. Let them whisper. If they want madness, I will give them madness that will echo through the generations. Let them carry my name to their dreams—let the ancestors hear my wahala and tremble.