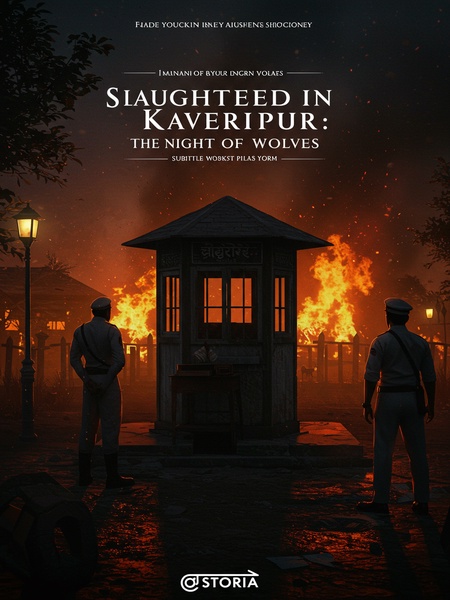

Chapter 1: The Smell of War

The air in Kaveripur that morning smelled of burnt plastic, diesel, and a fear thicker than the April humidity. Somewhere in the distance, a faulty tube-light buzzed, fighting against the dawn. The city’s usual scents—the frying pakoras from the corner stall, the sharp tang of incense at the temple—had been replaced by the acrid stench of something unnatural.

You could hear the far-off rattle of machine guns, the echo punctuated by the never-ending bark of stray dogs. Mothers pressed their children to their chests, murmuring Hanuman Chalisas and Ayat-ul-Kursi under their breath, their bangles clinking with every shiver. The city, once alive with chaiwalas calling out and jalebi vendors on every corner, was now drowned in a silence broken only by sudden, sharp cries of terror and the metallic clang of a distant shutter slamming shut.

If you hid at home, soldiers stomped up the staircases of old buildings, their boots thumping, voices echoing through thin plaster walls. Each family in every flat held their breath, as if the next exhale might betray them. Grandfathers pressed trembling hands over the mouths of crying infants. His thumb traced the child’s cheek, a habit from the days when lullabies were enough to quiet the night.

The soldiers shouted names from ration cards and voter lists, sometimes mangling them, sometimes twisting them into cruel jokes. Every syllable felt like a death sentence waiting to be called.

If you tried to escape, you’d see guns mounted on rooftops. Snipers lounged behind solar water tanks and satellite dishes, their rifles glinting in the harsh sun. Someone next to you would mutter, "Bas, our time is up," dragging his son behind a pile of bricks. The dry thud of a body hitting the ground was a faraway punctuation—someone else had failed to outrun fate.

Waiting for rescue? Even when the peacekeeping troops arrived, people gathered in the gullies, hope flickering in their tired eyes. Children strained at windows, and someone lit a diya in anticipation. "UN ki gaadi aa gayi, beta!" But the hope was crushed as news came—the peacemakers too were slaughtered, their blue helmets another splash of colour among the tricolour flags trampled in the mud.

Stock up and survive? The siege lasted five years, but Maggi noodles only lasted two. Tiffins emptied quickly, pulses and rice stored in tin boxes finished in months, not years. The stench of rotting vegetables in shuttered markets became as familiar as the sticky warmth of April in the plains. Aunty next door said, "Maggi toh do saal mein khatam ho gayi. Ab kya khayenge?" and everyone looked away, unwilling to voice the answer.

The answer could only be: your own relatives and friends. The thought was unspeakable, but as days turned into months, people grew gaunt and hollow-eyed, and you understood that hunger could strip away even the deepest taboos.

This was not fiction. This happened in Asia at the end of the 20th century—in Kaveripur, a modern city that had just hosted the National Games. The same Kaveripur where children played gully cricket till dusk, old men argued politics over cutting chai, and Imran’s mother sent halwa to their Hindu neighbours every Diwali, with Arjun’s family returning the favour on Eid. Stadium lights were cold now, medals gathering dust in abandoned homes.

The massacre lasted five years while the so-called civilized societies of Europe and America turned a blind eye. Neighbours huddled in darkened rooms, tuning old radios for international news, only to hear silence. "Europe walon ko kya farak padta hai? Apni toh koi sunta hi nahi," someone would say, the silence heavier than a power cut at noon.

April 5, 1992: the day before the Kaveripur massacre began. That day, the city simmered with tension. Posters fluttered on the walls—some torn, some with Bollywood stars’ faces—while the smell of sweat, cheap incense, and frying oil mingled in the air. Rumours buzzed between tea stalls, WhatsApp pings and radio snippets passing like wildfire. Everyone seemed to be waiting for something to break.

The city was fighting for independence, trying to break free from Dhanpur’s suffocating rule. Old people remembered stories from Partition, but for the young—students like Arjun—this was the first taste of real struggle. Hope flickered like a diya in the monsoon wind, casting its fragile glow over every whispered plan.

Dhanpur’s response was simple, brutal, and efficient: they labelled the citizens of Kaveripur as separatists, then used the army to choke the city so tightly not even a drop of water could escape. Highways blocked with sandbags, checkpoints sprouting overnight, phone lines dead except for those with secret connections. Even the milkman’s cycle was stopped at the barricade.

The leader of the Dhanpur army ordered: if Kaveripur is still fighting for independence tomorrow, the entire city will be wiped out. His voice, broadcast on Doordarshan and local FM, was calm as cold steel. "Agar koi bhi aazaadi ki baat karega, toh poore shehar ko mitti mein mila denge." The words sent a shiver through every mohalla.

Not a single living person left—let’s see how you’ll hold an independence referendum then. Mothers hid their children, old men drew their curtains, and young people, ever hopeful, whispered plans late into the night. But the fear was everywhere, like the smell of smoke clinging to skin.

At this time, Arjun—still a university student—joined a hundred thousand Kaveripur citizens to march and protest. He ironed his only white kurta, borrowed Imran's tricolour scarf, and stepped into the sea of faces outside his hostel. The crowd pulsed with slogans, the sound of conch shells, dholaks, and hope that refused to die.

They didn’t realise they were lambs waiting to be slaughtered. Hope shone in their eyes, naive and stubborn. The city square echoed with "Vande Mataram!" as arms linked and voices rose, drowning out the thunder of army trucks rumbling at the edges of town.

They tried, with the fragile strength of ants, to defend a precarious peace. Hands squeezed, water bottles passed, a protective arm around a younger sibling—small acts became acts of quiet bravery. The unity was real: Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, all singing "Jana Gana Mana" together at the top of their voices. Old men wiped their eyes. "Dekho, yahi toh asli Bharat hai."

Outside, the Dhanpur army had imposed a blockade and curfew. Loudspeakers crackled with the indifference of government voices. Gunfire punctuated the night, temple bells cut short by sirens. The city shrank inward with every passing hour.

Whispers filled the lanes: "Aadhaar card sambhal ke rakhna!" "Bas, ab toh Allah hi bachaye." People hid documents in rice jars, under mattresses, wherever they felt safest.

To pave the way for slaughter, the Dhanpur army had already practiced massacres, calling it “population cleansing.” Every neighbourhood had stories: the school in Sector 7, the temple by the ghat now blackened by fire. Eyes flicked to the shadows as stories exchanged in low voices.

The phrase “population cleansing” brought back bitter memories—Jallianwala Bagh, Bengal famine. "Angrez chale gaye, lekin soch abhi bhi yahin hai," sighed the elders. In living rooms with faded family photos, people wondered if things had really changed since 1947, or if the same hatreds now wore new uniforms.

The besieging army claimed to believe in Greater Dhanpurism. Ultra-nationalists, saffron flags, slogans that twisted patriotism into poison. Local goondas strutted with lathis, as if beating up neighbours was now an act of national service. What they hated most was a city like Kaveripur, where every mohalla was a patchwork of Gurdwaras, mosques, and temples standing side by side. Hate was whispered, then shouted, then blared from loudspeakers at every crossing.

Their leader: Dr. Bhaskar, a neurologist in a spotless Nehru jacket, voice cold as the steel tumbler in his hand. On TV, he switched from English to Hindi, his words slicing through the air. "Such a smart man, and yet so much hatred?" neighbours muttered. He scribbled plans on napkins while sipping filter coffee, his eyes shining with a fanatic's fire. His followers called him a visionary, but most saw a monster with a medical degree.

In homes lined with old NCERT books, teachers shook their heads. "Padhe-likhe ho kar bhi pagal ho gaya," disbelief mixing with fear. "Hum sab ek hi mitti ke hain," declared the old Imam, the pujari nodding in agreement. Kaveripur’s unity ran deep—kids didn’t know each other’s castes, only whose mother made the best aloo paratha.

Politicians tried to incite, but people rolled their eyes. "Kuch aur try karo, bhai. Yeh purani baatein ab nahi chalti." Sikhs tying turbans for Muslim neighbours, Hindu girls borrowing scarves from Christian friends. "We are Kaveripuris first," was the only slogan that mattered.

The ultra-nationalists changed tactics—sending infiltrators in mismatched clothes, faces covered with gamchas, to seize city hall. The city hall clock, once a source of pride, now tolled in warning. Officials who refused to cooperate were taken hostage; Muslim officials thrown from windows. The news spread: "Woh Imran Uncle, jo har Eid pe mithai laate the, unko bhi..."

At 5 p.m., students led a grand march to city hall, unaware of the trap. Marigold garlands, sweets in newspaper, hope as painful as a wound. The city clock struck five, and the mayor’s body hung from a street lamp. Some stood frozen, mouths open in silent screams; a child’s cry became the signal for chaos.

The marchers scattered, hopes bursting like soap bubbles. Chappals lost in the stampede, dholaks rolling down the steps, a discarded flag trampled in the mud. The rioters had no intention of letting these “heretics” go—they wanted to teach a lesson. Hatred burned in their eyes; someone screamed "Bhag jao!" but there was nowhere to run.

Machine guns, already prepared, opened fire. The staccato sound echoed off old stone, mingling with screams and prayers. Smoke curled upwards, carrying with it the city’s dreams. Students in front fell like ripe sugarcane before the harvester. White kurtas turned red, slogans died on young lips. Mothers searched for their children, calling their names into the chaos.

Arjun, being short, escaped by luck. Someone shoved him down as a bullet whizzed overhead. He crawled between bodies, his heart thudding so loudly he feared it would give him away.

His father, Kaveripur police chief, led his men in a desperate counterattack, firing back and rescuing the wounded. "Cover the children! Move them behind the statue!" he shouted, his own uniform soaked in sweat and dust.

Now, everyone understood: war had broken out. Even the smallest children grasped it. The innocence that had protected Kaveripur all these years was gone in a single day.

Continue the story in our mobile app.

Seamless progress sync · Free reading · Offline chapters