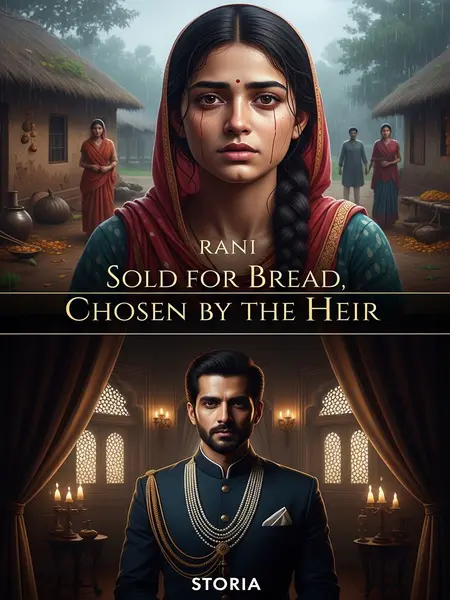

Chapter 2: A Gajra and a Goodbye

On the day I left home, my mother fainted from crying so many times her hands shook as she pressed her only dowry—a velvet gajra—into my palm. The scent of sandalwood clung to it, and the golden thread was worn thin. Her bangles clinked as she clutched my hand, the metal digging into my skin. She wiped her tears with her pallu, then tucked the money I’d slipped her into her blouse, casting a furtive glance over her shoulder. I couldn’t let myself cry; I just held her, whispering, “Ma, main wapas aaungi. Bhaiya aur Guddi ka khayal rakhna.” Outside, the world went on—vendors shouting, dogs barking, the lane indifferent to our sorrow.

I told her, no matter what, she had to raise my younger brother and sister well.

She nodded, her lips trembling, and kept repeating, “Tu mera maan hai, beta. Tu ja, par apne bhai-behen ko kabhi mat bhoolna.” My brother stood by, thin as a reed, eyes wide and confused. My little sister clung to Ma’s sari, hiccuping. I tried to stand tall for them, though my heart felt hollowed out with every step away from home.

The rain was relentless. My father was still in the city. My mother stood shivering in her soaked saree, my siblings pressed close to her, watching as I climbed onto the bullock cart. The wooden wheels creaked through the mud. “Rani, khayal rakhna apna!” she called, her voice torn by the wind. I turned back one last time, memorising the sight of her arms wrapped around my siblings, the rain blurring everything except the ache in my chest.

As the bullock cart rumbled away, the muddy lane was slick beneath the wheels, and the air was thick with the smell of wet straw and burning dung cakes from distant hearths. The wind and rain stung my eyes until I could barely see.

I kept glancing back, hoping for one more glimpse of my home. Each jolt of the cart made my small bundle shake. I pressed the gajra to my nose, breathing in Ma’s scent, letting my tears mix with the rain until they were one and the same. For the first time, I understood what it meant to leave a part of yourself behind.

There were twelve girls packed in with me, all from our village or nearby. Though we’d been sold, at least now we could eat. Those who had the strength to sell their daughters never did so lightly.

We huddled close in the cart, sharing stale rotis and dry gur. Some cried softly at night, others stared blankly at the wooden beams above. One girl began to hum a lullaby from home, her voice trembling. Another tied a black nazar thread around my wrist, whispering, “Yeh tujhe buri nazar se bachaye.” The older girls braided the younger ones’ hair, sharing bits of soap and kindness. Sorrow had its own sisterhood.

We passed the days with talk and laughter where we could. I listened more than I spoke, uncertain of what waited for us.

Some girls spun dreams aloud—of city work, of sending money home, of returning one day with glass bangles jangling. Their chatter soothed me. At night, we lay pressed together, warmth and whispers the only comfort. The traffickers barked orders but left us alone. There was food, and that was a blessing—however small.

The journey was long and hard. Over a month later, we reached Lucknow, and spring had come.

We travelled by lorry, by train, sometimes by foot—crowded, tired, waiting for hours at nameless stations with flies buzzing. My feet blistered and healed, and then blistered again. Mango blossoms scented the air, signalling winter’s end. Lucknow was nothing like Kaveripur: its lanes buzzed with scooters, and the shops glittered with things I’d only seen in movies.