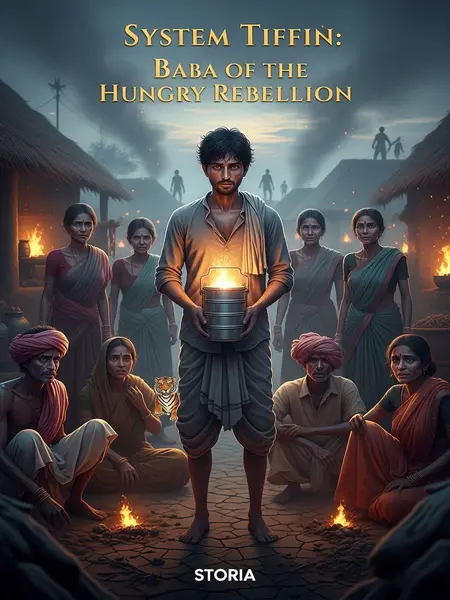

Chapter 5: Tragedy and the Tiger Token

After Ramakant’s visit, routine returned. A month slipped by before I noticed.

Still, the bathing issue remained. No soap meant dirt was now a second skin. I’d have to solve that soon.

Nandu now stuck to me like glue. At night, men sometimes paced outside the tent—maybe full stomachs led to sleeplessness?

Some laborers had begun gaining weight, faces filling out, no longer skeletons.

Five days ago, Ramesh had left for home and hadn’t returned. I worried, but kept quiet.

I’d scouted the hills—bamboo everywhere, but without iron tools, what could I do?

I needed knives—real iron ones. Life was too tough without them.

Just then, Ramesh returned, face shadowed by grief.

I asked gently, “Kya hua, bhai? Sab theek hai na ghar par?”

Tears welled in Ramesh’s eyes. “Raja ne pitaji ko saja-e-maut de di. Amma bhi shock se guzar gayi. Chhoti behen gayab hai.”

A chill ran down my spine. “Kaise hua?”

He gritted his teeth. “Pitaji ne Raja ko samadhi banane se roka, kuch kadve bol diye. Raja ne gusse mein maar dala.”

What could I say? Feudal laws made human life cheap.

He went on, “Is saal akal pad gaya hai. Sarkar ke paas daane nahi. Project site par bhi hungama hua. Baba, taiyyar raho.”

A peasant uprising? My history teacher had said—every uprising brings rivers of blood.

We were far, maybe safe. Who knows?

Ramesh pulled out a tiger-shaped gold amulet. “Pitaji ne bola, yeh token aapko de doon. Aap samajh jaoge kaise use karna hai.”

My mind spun. “Yeh kis kaam aayega?”

“Fauj ki command dene ke liye. Pitaji ke pass teen sau ghode wale the.”

My head reeled. If I had that force, would I be called a rebel? For now, best to take things day by day.

I sent a nimble boy to scout the main site. If things got bad, he’d bring our people to the hills. With my system, hunger wouldn’t be an issue.

I gave him six Set As—more precious than gold here—and wished him luck.

But unease gnawed at me.

That night, the runner returned, pale and shaken.

“Kya hua?”

“Mahaul kharab hai. Jang ho gayi—laashen bikhri thi, khoon ki nadiyan beh rahi thi.”

“Kaun lad raha tha?”

“Maloom nahi. Sab chup tha. Koi zinda nahi tha.”

My thoughts raced. The workers must have rebelled, looted, then scattered. No wonder Ramakant had warned me—the nation was on the brink.

No time to waste—I needed more supplies.

I gathered Ramesh and ten men, heading to the main site.

“Wahan armoury hai?”

He nodded. “Dikhaata hoon.”

Strengthened by tiffin meals, we reached in a day. The sight was horrific—bodies everywhere, the smell overpowering.

Nandu handed me water. “Rajya bane ya gire, aam aadmi hi pista hai.”

Ramesh murmured, “Rajya mein vikas ho ya patan, janata hi dukh uthati hai, baba. Aap aam insaan nahi ho.”

Not wanting to talk, I led them to the armoury.

Nandu whispered, “Baba, inke kapde utar lein?”

I shook my head. “Mritak ki izzat honi chahiye.”

The granary was bare, armoury stripped, but we found five steel knives and three spears.

We took everything—iron pots, hoes, rakes—anything with metal.

And luck! Four horses stood at the back, and nearby, four bullock carts.

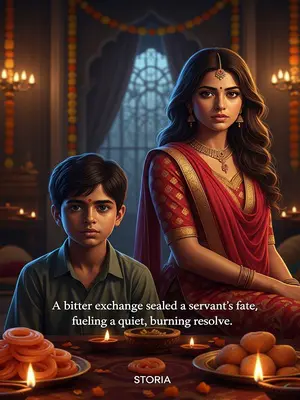

Bhaiya brought a young girl, no older than fifteen, shaking, feet bare.

I crouched, voice gentle. “Naam kya hai, beti?”

She bit her lip, silent. “Maa-baap kahan hai?” Still no answer. She looked lost—a frightened fawn. I decided she’d stay with us till we found her family.

We loaded everything—bedding, chappals, clothes, salt, atta, even a chakki, knives, and axe.

The girl, now in chappals, whispered, “Darwaze ke peeche ari hai.” Nandu fetched it—a new saw.

“Shabash, beta! Teri nazar tez hai.” She smiled, hiding her face in her dupatta.

We paused for lunch under a peepul tree. I gave her an A and C set.

She stared at the tiffins, unsure.

“Bhookh nahi lagi?”

She bit her lip. I gently pushed the food into her hands. “Sab khate hain yeh. Vish nahi hai.”

She clutched the dabba like treasure. I ate with gusto. Seeing me, she finally opened hers—chicken, palak, beans, rice, cola.

She used two twigs as chopsticks, ate a bite, and suddenly tears ran down her face.

I knelt. “Kya hua, beta?”

She sobbed, “Agar maa-baap ke paas yeh hota, woh bhookh se nahi marte.”

My heart clenched. “Toh ab tum jeeyo, beta. Khub khao, khush raho.”

She nodded, wiping her tears, then glanced at me, smiled shyly, and quietly offered her chicken leg, quickly looking down and hiding her face in her dupatta after I refused.

I smiled, refusing. “Tu kha le. Mera pet bajra roti se hi bharta hai. Cola pee le, ladkiyan ko pasand aata hai.”

Nandu laughed, “Hamare baba toh bajre ki roti aur cola pe zinda hain.”

She looked puzzled, but accepted. Here, bajra was luxury.

After lunch, I called a meeting. With the country burning, it was time to gather everyone’s families—no one should be left behind.

I shared the plan. Some wept quietly—families meant everything.

But Rajpur was far, and tiffins wouldn’t last. We’d need dried rations and plans.

At the cave, after unloading, we left the carts at the hill’s base. “To get rich, pehle road banao,” I quipped. “Aur bachchon ki sankhya kam rakho, ped zyada ugao.”

No more shramdaan. Now, survival was our work.

Everyone wanted to fetch their families, but I made them rest.

Inside, I found the girl—now clean, fingers twisting her dupatta.

“Nandu kahan hai?”

“Jab main andar aayi, woh samne chala gaya,” she whispered.

Suddenly, she bowed, hands folded. “Baba, agar aapko manzoor ho, main aapki saathi ban sakti hoon.”

I burst out laughing. “Saathi? Arre, feudalism ne kya kar diya hai!”

She blushed, “Main abhi bhi kuwari hoon.”

“Bas, bas! Kitni umar hai?”

“Pandrah.”

“Naam?”

“Chunni.”

“Chunni, pandrah saal. Khana khao, khelo, khush raho. Saathi ki baat mat socho.”

Her face fell, but I softened. “Tent mein mere aur Nandu ke saath raho, saaf safai mein madad karo. Theek hai?”

She nodded, her sad eyes turning to little moons.

Outside, men gossiped.

“Lagta hai baba bhi insaan hai—aurat ka shauk hai.”

“Accha hai, kam se kam moh maaya toh hai.”

“Meri behen hai, solah ki, agle baar launga.”

“Teri behen, wah! Chehra dekh ke toh bandar bhi darte hain!”