Chapter 1: Boasts and Bunks

When I was in junior high, my deskmate was a girl who loved to boast. She claimed her family owned a huge 2BHK flat—in a city like Mumbai, where most of us squeezed into cramped one-rooms, a 2BHK sounded like full-on filmi luxury. She’d talk about their separate piano room, how her mother adored her, always took her advice before buying their Maruti car, and that they were planning a holiday to Lonavala. She even claimed she’d never washed her own underwear until she was thirteen. Her stories always ended with some lavish detail, like how her mother would wake up at five to peel fresh Safal corn for her breakfast.

Sometimes, when she'd start off with these stories, I'd just roll my eyes and mutter under my breath, 'Yaar, as if!' I fiddled with my school badge, pretending to focus on my tiffin. She’d look at me with that stubborn pride, acting like it was no big deal, but the rest of us knew this kind of boasting was mostly for show. Still, deep down, I wondered what kind of life she’d seen to need such stories.

But her hair looked like it had survived a Holi gone wrong, uneven and wild, like the street dogs near the railway tracks. She couldn’t afford sanitary pads at the hostel and always carried a certain smell, ate just one meal split between breakfast and lunch, and the cuffs of her trousers nearly reached her knees.

Even in our stuffy hostel room, where the ceiling fan barely worked and the smell of Maggi lingered, her poverty stood out. Her hair—uneven, frizzy, as if the local barber had used kitchen scissors. The girls whispered about her, noses wrinkled at the scent she carried; she’d stuff her clothes with bits of old cloth instead of buying pads. At lunch, she’d quietly break her bun into half, saving a piece for later, and the way her faded salwar hung, it was obvious she was making do with hand-me-downs or whatever the school charity box coughed up.

She was so poor, there was nothing left for her to hide.

Sometimes, when the others laughed, I caught myself glancing at her and wondering how she managed to hold her head up every day.

It was an open secret, the sort people gossiped about near the water cooler or in the hostel corridors. Someone even made a meme about her in the class WhatsApp group, calling her “Little Shell”—like she was just a cover with nothing inside.

Everyone disliked her.

We Indians can be sharp-tongued when we sense weakness, and nobody wanted to be seen with her. She was an easy target for jokes and taunts—the sort whose presence made others shuffle away.

Once, while I was listening to music, she started boasting again. I was so irritated that I asked, “Oh, so you’re like this now because your mum is dead?”

She slapped me and made my nose bleed.

“Don’t you dare talk about my mum! She’s the best, okay? You don’t know anything. I’m like this now… because my mum didn’t see. If my mum saw—then it would be fine.”

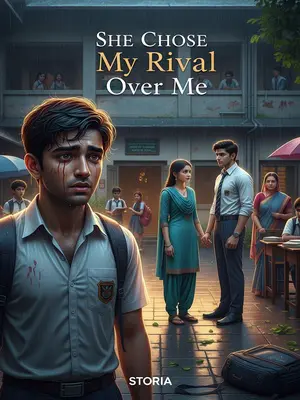

The slap echoed in the classroom, drawing everyone’s attention. She wiped her tears with the back of her hand, like Amma used to do after a fight with the landlord. I clutched my nose, blood trickling down, shocked more by her words than the pain. Her eyes were fierce, cheeks wet, her voice trembling as she spat those words. For a second, all her boasting seemed to crumble, revealing just a scared, stubborn girl desperate to believe her own stories.

I pinched my nose and jumped onto the creaky wooden desk, ignoring the chalk dust that flew up: “Fine, fine, then call your best mum in the world to pay my medical bills, come on.”

I tried to save face, making a scene. The boys hooted and the girls tittered, but inside I felt something twist—guilt or anger, I couldn’t tell. “Go, call your mummy,” I taunted, though I knew even then that there would be no one coming.