Chapter 3: Arjun Singh’s Stand

First, let’s talk about the founding of the first Indian National Army battalion: the Fourth INA Battalion.

The name is legend, spoken with pride at army reunions and school competitions. Even today, at Republic Day parades, an old veteran might boast, "I served in the Fourth INA." Their eyes shine, remembering when hope was as fragile as it was powerful.

In 1937, the British cracked down on Congress, launching the April 12 Counter-Revolutionary Operation, imprisoning leaders and activists. The Party was caught off guard, betrayed, thrown into confusion. Heated debates erupted—what to do now?

News travelled slowly—by telegram, by word of mouth, or hurried notes at railway stations. But the panic was instant: suspicion, fear, and the sense that the old ways wouldn’t work anymore. In every city and village, people waited, listening for the ticking clock or the distant tramp of police boots.

In the film "The Founding of an Army," some still want to copy the Soviet model—urban uprisings—while pragmatic leaders like Netaji argue for retreating to rural areas, relying on peasants for the revolution.

Netaji, under a banyan tree, argues passionately as comrades fidget. These debates weren’t just politics; for those living through it, every choice was life or death. The idea that India’s future would be shaped in dusty fields and small towns was radical—and, as history proved, absolutely right.

Against this backdrop, the Party organised the Lucknow Uprising and the Autumn Harvest Protest. But the enemy’s strength was overwhelming; both failed.

For days, the air was heavy, buzzing with the tension of unsaid words. The brave but unprepared clashed with colonial police. News of defeat spread fast—families waited in dread, mothers lighting lamps and praying for sons, even as the city outside echoed with sirens.

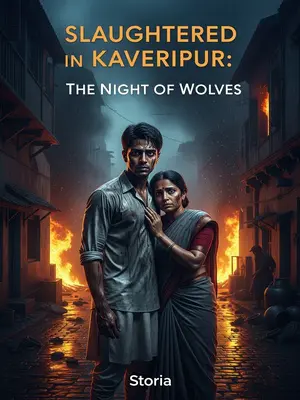

After the Autumn Harvest Protest failed, Netaji assessed the situation, dropped the plan to attack Kanpur, and led the remaining troops to Kaveripur in October 1937. There, he dealt with warlords Devendra Singh and Raghav Rao and finally secured a base.

This retreat was a regrouping, not a surrender. The march to Kaveripur was grueling—mud, hunger, betrayal always close. Netaji led by example: first to rise, last to sleep, always checking on his youngest soldiers. The Kaveripur camp was just huts and tents, but it became the movement’s heart.

With Kaveripur secured, Netaji prepared to meet General Arjun Singh. But how did Arjun arrive?

Every veteran in Kaveripur knows the tale: Arjun Singh, dust-covered, exhausted, arriving with a handful of loyal men—uniforms torn, spirits unbroken. The meeting with Netaji was marked not by speeches, but a handshake and a glance. This quiet moment was the start of something extraordinary.

Ask any army old-timer: "Woh Arjun tha toh sab kuch mumkin tha." His journey to Kaveripur is legend, taught to young cadets as a lesson in perseverance and sacrifice.

The Lucknow Uprising’s main force was Captain Yusuf and Major Harpreet’s troops. Arjun Singh wasn’t prominent at first. Later, after withdrawing from Lucknow, the revolutionaries suffered heavy losses in the south. At Sanheba in Maharashtra, the troops split, and Arjun Singh led 3,000 men to hold off the enemy and cover the retreat.

The fields of Sanheba were muddy with the first monsoon rain, and the cries of peacocks echoed even as gunfire crackled in the distance. Arjun’s orders were simple but brave—"Hold the line, no matter what." His men, many barely out of their teens, looked to him for strength. Campfire songs would later remember these days—proof that courage can turn retreat into legend.

Arjun Singh was taking on a suicide mission, facing over 20,000 under Colonel MacIntyre. He knew survival was nearly impossible, but accepted the task without hesitation.

In that moment, he became more than a soldier—he became a symbol. Survivors’ letters recall Arjun, even as bullets flew, moving from trench to trench, patting trembling shoulders, whispering, "Zinda rahoge toh desh ke kaam aaoge!"

The southern force was almost wiped out at Tangkhed. Leaders fled—Nehru and Rajaji to Bombay, Captain Yusuf to Goa, Lakshmi Sehgal to Chennai, Major Harpreet to Punjab.

Families waited anxiously for news. These days, it’s WhatsApp forwards, back then it was the anxious wait for a telegram. In many homes, mothers kept lamps burning for sons who might never return. Yet, from these ashes, hope slowly grew—each leader scattering seeds of revolution in a new corner.

The uprising failed; leaders were scattered. No one could say what to do next.

For weeks, confusion reigned. Some lost faith, others grew more determined. In every tea stall and village square, the question was the same: "Ab kya karein?" It was a time of uncertainty, but also new beginnings, as fresh leaders stepped forward.

Arjun Singh, holding out at Sanheba, was heavily outnumbered and eventually had to break out. Morale was rock bottom. Many said, "The main force is gone, why bother? Let’s disband too."

Some stared at their torn chappals, ashamed to meet his eyes, but no one spoke the words. On those long, hungry marches, Arjun Singh kept the spirit alive. "Azaadi ki ladai mein kabhi haar nahi maanni chahiye," he’d say, voice raw but determined. His conviction gave others hope.

Numbers dwindled. By late October, only Arjun Singh remained at division level, and only Kunal and Amit at regiment level. The unit was falling apart.

At night, as the group huddled under the stars, the sense of loss was deep. Many wondered if their struggle would be forgotten. But the bond between those who stayed only grew. Kunal and Amit, once mere colleagues, became brothers-in-arms—united by suffering and an unspoken promise.

At this critical moment, Arjun Singh, with unwavering faith, inspired the remaining officers and soldiers. "Jo sath aana chahta hai, woh aage badhe." No grand speeches—just a call to courage. One by one, men stepped forward, enough to carry the flame onward.

The result: Arjun Singh, with just 800 left, braved endless hardship to reach Kaveripur and join Netaji. Among the sparks he preserved were Rohan, a company commander; Kabir, a guard squad leader; and Amit, regimental instructor.

Their journey was epic—crossing rivers, hiding from patrols, scavenging for food. When they reached Kaveripur, they were greeted as heroes. Netaji himself embraced Arjun. Old-timers say the cheers that day could be heard for miles.

Who could have imagined these few would, twenty years later, command the three great campaigns of the War of Independence?

History is shaped not by those born to greatness, but by those who refuse to be broken. Rohan, Kabir, Amit—now just tired, hungry men—would one day be names on memorials. It’s a reminder that greatness is born in the quietest moments.