Chapter 1: The Legend of Midnight Music

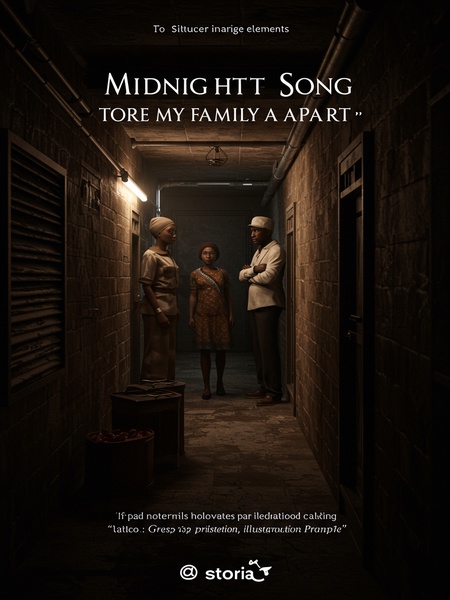

Ask any old Ibadan man about 1956, and if the wind is right, he’ll lower his voice and say: “That was the year midnight music nearly finished us all.”

You go hear am for Dugbe joint—“Omo, you never hear about that night?” The tale is still whispered among some old-timers in Ibadan, whenever the midnight breeze carries a hint of music. The story has become part legend, part warning—a tale that chills the blood on nights when the moon hangs low, and the shadows stretch long across the city streets.

The film no fit show wetin really happen finish—dem just manage am for cinema. The real-life event was so frightening, even the bravest actors refused to talk about it fully.

Survivors never talk am, except to whisper small prayer or rub kola nut for luck. The movie softened the sharp edges of the truth; what truly happened that year would have sent most people running for deliverance.

This incident was what led to the creation of Nigeria’s own Unconventional Incident Handling Unit, popularly called Division 749. Of course, it has an official name, but because of security reasons, that one is not made public.

The official name is locked away in files with red covers in Abuja, only whispered among those who deal with things ordinary people—abeg, no ask—go fear. On the streets, people just call them Division 749, or sometimes, if they’re being careful, “those people that handle wahala wey no be for human mouth.”

Before we talk about what happened, let me first explain how these mysterious incident-handling departments have evolved throughout Nigerian history:

Oya, let’s settle down—grab your stool, make sure your ears are open. This isn’t the kind of thing you’ll hear in any schoolbook, but our people say, if a story is strong enough, it will survive even when the wind tries to carry it away.

If you check most research on the history of the old kingdoms and colonial era, you won’t see much about this topic. But just because academics don’t focus on it doesn’t mean there’s no evidence. In fact, old documents and recent archaeological findings reveal a secret most people don’t know: as far back as the Oyo Empire, there was already a nationwide agency for handling supernatural and abnormal matters. This organization reached down to local chiefs and councils, and it was headed by none other than the Royal Astronomical Guild.

Some ancient Ifa verses, coded letters in the palace archives, and even the faded ink on cowrie-strewn scrolls tell the story—though only if you know how to read between the lines. Oral historians in Oyo and Benin still recite tales of strange visitors to the palace, men and women whose footsteps seemed to vanish as soon as they left the earth floors of the royal court.

This institution hid deep inside the palace, even more mysterious than the famous royal guards. The entry-level officials were all called Masters of Earth and Sky, and their family records were separate from the four main types in the old census—farmers, warriors, artisans, and traders. Instead, they had their own special category called “Spirit Households.”

To belong to a Spirit Household was to be marked, almost like being born with a special birthmark. At festivals, these families sat apart—neither fully in the world of the living nor the dead, but somewhere in-between. It is said their children learned to see what others could not from the time they could walk. Their compounds always got kolanut trees, and neighbours avoid their gates after sunset.

Records show that the Spirit Household system started as far back as the time of Alaafin Sango. In the 25th year of the reign of the last Oyo king before colonial rule, the king, after taking over new lands and calling himself the Defender of the Realm, followed the system of the Benin court and set up the Royal Historian’s Office, which handled astronomy, the calendar, and spiritual matters. He put Baba Ifedayo in charge as the first director, the Chief Historian.

Baba Ifedayo’s name still lingers in the prayers of some old families—“May wisdom guide our steps, as it did for Ifedayo.” The merging of Benin and Oyo ways created a powerful blend, making the palace a center not just of governance, but of spiritual authority. Elders say Baba Ifedayo could read the stars and the bones, a man who saw the turning of seasons before they arrived.

The “Chronicles of the Oyo Kings” records: “On the day of the great festival, the Royal Historian’s Office was established, the Chief Historian was appointed, along with subordinate officials such as the Record Keeper, the Oracle Scribe, the Sky Reader, the Keeper of Sacred Drums, the Spirit Messenger, and the Assistant to the Chief Historian, in charge of the calendar and spiritual supervision. Baba Ifedayo was appointed as Chief Historian.”

The chronicles, written in palm-oil-stained ink, speak of processions where the Keeper of Sacred Drums would beat rhythms no ordinary ear could follow. The Oracle Scribe’s job was to write down messages from the unseen, while the Spirit Messenger was rumoured to travel between worlds in his sleep.

The king didn’t just create this out of nowhere. For more than two thousand years of West African civilization, such a department was always there in the central government, in charge of astronomy, calendar calculations, geomancy, and handling extraordinary events.

It was a legacy passed down in secret, not just by word but by ritual—every coronation or festival, a portion of the ceremony would slip into mysterious silence, while certain elders circled three times, poured libation, and muttered words nobody else dared repeat.

During the Nok and Ife eras, the royal court had the post of Chief Historian, responsible for these things—like the famous Scribe of Ile-Ife. After the Benin and Nupe periods, the historian side of the office was separated, leaving them mainly in charge of calendar, geomancy, and supernatural matters.

Among the Nok, terracotta figures were placed at crossroads to watch over travelers. In Ife, the scribe’s stylus was considered as powerful as a priest’s staff. When Nupe influences came, new methods of recording omens and lunar cycles mixed with the old ways, but the core remained—a hidden hand guiding kings through storms both physical and spiritual.

By the time of the Kanem-Bornu and Hausa city-states, the government set up the Royal Astronomical Guild, which later became the Palace Council of Elders. When the colonial powers came, they first set up the Royal Historian’s Office, which was later officially renamed the Royal Astronomical Guild after the formation of the protectorates.

In Kano and Maiduguri, elders would gather under the baobab tree on moonless nights, consulting cowries and stargazing with polished stones. The British, of course, tried to codify everything, stamping new names on old offices, but the real work remained hidden in back rooms and whispered consultations.

This shows that, for thousands of years, the department in charge of special affairs in Nigeria hardly changed. Before colonial times, it was always directly managed by the institution in charge of astronomy and the calendar.

Even with colonial rule, the pattern only shifted on the surface. Old hands say that while white men filled forms and shuffled papers, true decisions were still being made by men and women whose eyes saw further than the horizon.

After independence, the job of handling mysterious and supernatural events was given to the Intelligence Bureau. Specifically, the Second Section, Second Division, Second Group of the Intelligence Service handled these things, dealing with secret societies, religious affairs, and supernatural phenomena.

This was the era when people started hearing whispers about "Special Assignment," and you’d see certain government jeeps parked in places they had no business being. Officially, everything was about national unity and development, but in the shadows, Division 749’s roots were growing.

Below is the organizational chart of the Intelligence Service, with the department for these matters marked in red:

Picture it—a faded, typewritten chart locked in a cabinet somewhere in Dugbe. The red mark, according to the few who have glimpsed it, is small but unmistakable, like a drop of palm oil on white cloth: once you notice, you can’t unsee it.

This is the main historical background for the creation of Division 749. Now, let’s talk about the strange event that started it all. As for the mysterious Masters of Earth and Sky system of the Oyo Empire, we’ll come back to it later.

Some secrets refuse to stay buried; even as we move forward, the echoes of old rituals and hidden offices still shape the present. But let us return to the night when the mask fell and Division 749’s story truly began.

Continue the story in our mobile app.

Seamless progress sync · Free reading · Offline chapters