Chapter 2: The Haunted Theatre of Dugbe

In short, the so-called Masters of Earth and Sky were the palace’s own ajọ̀gun hunters—sent to chase trouble wey pass ordinary eye. They were neither pastors nor imams, not chiefs nor ordinary people. Their job was unique, their organization strict, and they were a strange presence in the old society.

Their presence was often felt in the sudden hush at the market when they passed, or in the way elders would quietly close their doors at dusk on days when they visited. Even masquerades, bold as they were, gave way to the Masters when their work began.

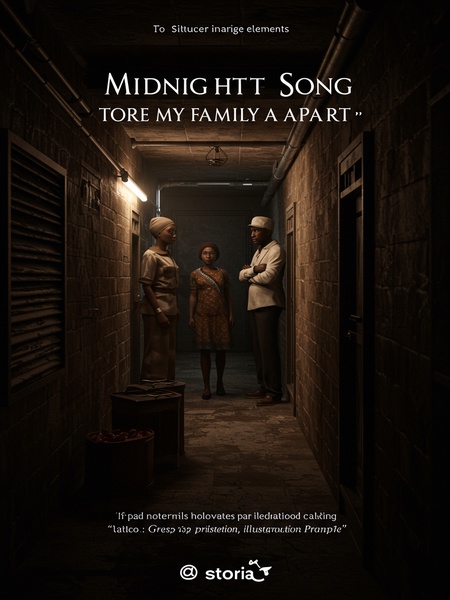

Now, let’s move to the 1956 “Song at Midnight” incident:

Listen well—because this part, ehn, is where ordinary turns to extraordinary. Ibadan in the 1950s was alive with the sound of drums, the laughter of children, and the cries of traders calling out their wares. Drums from Oje market, smell of fried dodo, and boys playing ten-ten under the streetlight. But behind the brightness, shadows sometimes danced where eyes dared not linger.

After independence, all the local theatre troupes were reorganized into proper drama companies. In Ibadan at that time, several troupes were set up one after another, including Ibadan Drama Troupe No. 1, No. 2, No. 3, and the Oluyole Drama Troupe.

The competition was fierce—each troupe boasting their best drummers, finest dancers, and the most gifted storytellers. Theatre then was not just art, but a battleground of reputation. Old men at joints would argue over who was the better lead, while children tried to sneak into rehearsals, hoping to see magic.

These troupes were later merged into the Ibadan City Drama Troupe, but in the 1950s, most still ran independently. The incident we’re talking about happened in one of these four troupes.

Which one? Omo, that part is still argued about in certain beer parlours. Some say it was No. 2, others swear it was Oluyole. But all agree—after that night, none of the troupes was ever quite the same.

To give you more details, one of the troupes recruited talents from all over the country and quickly grew so big that their original residence couldn’t contain everyone. The troupe had no choice but to ask the cultural department for more accommodation for the new members.

The new faces brought new energy—and new headaches. There were arguments over room space, jollof versus ofada rice, and whether the Igbos could outdance the Yorubas. But through it all, there was a sense that they were building something important, something that might one day be spoken of with pride.

Back then, it was still easy to find theatres in Ibadan, especially around Dugbe Market, which was a traditional spot for theatre lovers, full of stages. After checking, the cultural department gave the troupe an abandoned theatre in Dugbe, telling them to clean it up and move in.

The elders shook their heads when they heard the location. “Dugbe? That place wey dem say e dey chop spirit?” But who was listening? In those days, ambition often spoke louder than caution, and anyway, free accommodation was free accommodation.

This new theatre was in the Oke-Ado area near today’s Dugbe Market. It’s not convenient to mention the exact address, but knowing the general area is enough.

The building itself sat back from the road, with tall pawpaw trees swaying in the yard. Some say, if you looked closely at the gate, you’d see old chalk marks—a sign of previous attempts to drive out bad spirits.

With the new place ready, the troupe’s newcomers soon moved in.

They swept the floors, scrubbed the windows, and made jokes about ghosts. Some poured libation at the door for good luck. Others—mostly the ones from Benue and Rivers—hung charms above their beds, just in case.

The troupe members were happy with their new home. Not only was it in the center of town, it was also spacious. There was a stage in front, and at the back, a garden and a pond. Even though the pond water was stagnant, it was still a rare water feature in the city—a real luxury.

The garden quickly became a favourite spot for late-night gossip and quiet rehearsals. The pond, though a bit green and smelly, was the subject of many jokes—“Abeg, make you no swim inside o! Na so dem go carry you for inside bucket!”

Such a nice place made the newcomers very happy, and soon, work and daily life went back to normal. A keke napep would pass by the compound every morning, and the smell of akara from Mama Kemi’s bukka drifted in with the breeze.

Morning routines were simple: a few early risers fetched water from the borehole, while others queued for hot pap. The senior actors teased the juniors, and the whole compound felt alive with hope. In the evenings, someone would always bring out a talking drum, filling the air with rhythm as dusk crept in.

But none of them knew that this theatre had long been called a haunted house by the neighbours. In the middle of the night, strange singing often drifted from the garden stage. The neighbours, though a bit uneasy, were old residents and knew the theatre’s story, so they weren’t afraid.

One old mama hissed, “Dugbe theatre? Spirit dey chop there since my papa time!” These neighbours would sometimes spit three times when passing, or drop a bit of salt by the gate, old habits meant to ward off bad things. They believed that so long as you respected the spirit’s space, it would leave you alone. But to the new tenants, these warnings seemed like pure old-wives’ tales.

The new troupe members didn’t know any of this. The cultural department officials might have heard some rumours, but as civil servants, how could they believe in such superstitions?

After all, Nigeria was moving forward—there was no space for old fears in the new city. If anyone whispered about ghosts, the officials would just laugh and say, “Abeg, face your work!”

The incident happened on the third night after the troupe moved in.

That was the night the air felt heavier, and even the mosquitoes seemed to sing off-key. Some say a dog howled at midnight, and the streetlight outside flickered, but nobody noticed—until it was too late.

That night, all the troupe members, by some strange coincidence, had the same dream: someone was singing a lead female role aria on the stage in the house. The voice was clear and strong, every word accurate and sweet—obviously the work of a real master.

The song was so hauntingly beautiful that some woke up with tears on their faces. Others claimed they could still hear the last note ringing in their ears as dawn broke. But each one, thinking it was just ordinary dreaming, kept quiet.

Some say, if many people dream same dream for one night, something dey come. These details only came out later during the investigation. At the time, the troupe members thought it was just a dream and didn’t talk about it with each other.

Nigerians say, “If you dream bad thing, no talk am, e go pass.” Maybe that’s why nobody shared their strange night’s story—not knowing how deeply connected their experiences really were.

Not long after, the troupe was chosen to perform at the 1956 Independence Day cultural gala. To make sure they did well, the troupe not only carefully picked their show, but also did orientation with each member, telling everyone to focus fully on training and not slack off.

Rehearsals became serious business. Troupe leaders paced the aisles with canes and whistles, demanding perfection. “If you disgrace us, you disgrace your whole village!” was a common threat.

Continue the story in our mobile app.

Seamless progress sync · Free reading · Offline chapters