Chapter 3: Femi and the Midnight Master

A young man called Femi, who played the young male lead in the troupe, was also picked to perform. He would later become the prototype for the character Wale in “Song at Midnight.”

Femi was a bright-eyed dreamer from Akure, eager to prove himself. He was the kind of person who carried his mother’s prayers in his pocket and never turned down extra practice.

Wanting to do well, Femi worked hard, often practicing late into the night.

Even the lizards on the wall seemed to hold their breath, watching. He would rehearse lines in front of the cracked mirror in the green room, sometimes humming old tunes to calm his nerves. Other actors joked, “Femi, you wan turn to ghost with all this midnight waka?”

But as a newcomer, Femi lacked both experience and skill. On top of that, he was from another region and had trained in the Benin style, while Ibadan had already started using the Yoruba accent. No matter how much he tried, he always seemed a bit off.

His tongue stumbled over certain words, and he carried himself a little too stiffly for the local flavor. Even the costumers noticed—his sash never sat quite right. The others tried to help, but some quietly grumbled about outsiders getting choice roles.

One night in late March 1956, while practicing the Yoruba accent, Femi didn’t know when to stop and kept practicing till midnight.

The city had gone quiet, and only the distant cry of an agbo seller broke the silence. Femi was so lost in his lines that he didn’t notice the time until the lamp’s glow began to sputter.

At that time, the Ibadan dam wasn’t working yet, so most people still used kerosene lamps at night. As Femi practiced deep into the night, his lamp oil started to finish. He was about to get more when, all of a sudden, a man’s voice came from the darkness near the stage: “The way you sang just now wasn’t quite right.”

The voice was soft but commanding, with a lilt that spoke of years on the stage. Femi’s mouth went dry, and he almost dropped his script. His skin prickled with goosebumps. He looked around, expecting to see one of his friends playing a trick—but the room was empty.

Femi wasn’t sure if he’d really heard it. In his confusion, he saw someone quietly step out from behind the stage curtain.

The curtain barely moved, yet a figure emerged—a person whose movements were so smooth they seemed to float. The old wooden floor should have creaked, but not a sound was heard.

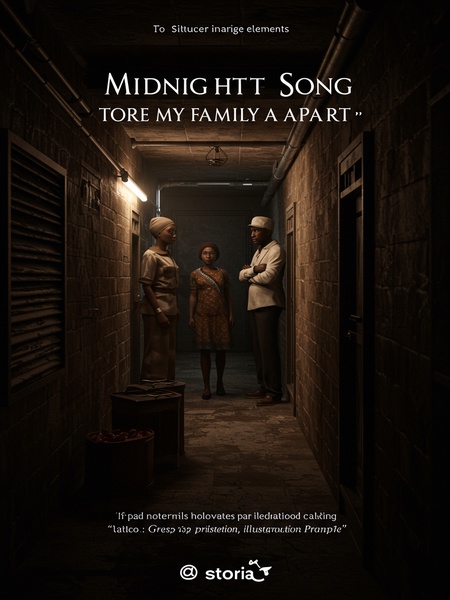

The figure wore an old-style lead female role costume from before independence. His face was half hidden in shadow, not clear, and when he walked across the wooden stage, his feet made no sound at all.

The costume shimmered in the half-light, heavy with old embroidery. The figure’s hair was pulled back in a way no modern actor wore anymore, and the only thing visible beneath the brow was a single, piercing eye.

Femi was so scared, he just stood there like a statue. The man said, “This line should be sung like this,” and then started to sing.

The air itself seemed to freeze. The man’s voice rose, carrying the exact lilt and rhythm that Femi had struggled to master. It was as if the stage itself remembered a time before anyone living was born.

That night, Femi had been practicing the classic aria “The Palmwine Calabash.” The mysterious man’s singing was much better than Femi’s—especially his Yoruba accent, which Femi found very impressive and useful.

It was the kind of performance that made the skin tingle and the heart ache—a perfect blend of story and song. Femi listened, spellbound, barely daring to breathe.

In theatre, you need a master to guide you if you want to improve. But in Ibadan at that time, there were only a handful of top artists, and unless you officially became their student, you couldn’t learn from them.

The world of theatre was closed, bound by respect and hierarchy. Even to ask for a lesson from a master without an introduction was to risk insult. Femi knew this better than anyone, and so his hunger to learn warred with his fear of the unknown.

As a newcomer with no connections, Femi didn’t have that chance. So when this mysterious man offered to teach him for free, Femi, even though he was scared, was also eager and grateful.

It was a temptation stronger than fear. Femi’s hands trembled, but he knelt small, right hand touching the ground, just as his mother taught him—eyes lowered in respect.

For the next few days, Femi waited until midnight every night for the mysterious man to appear.

He would sit in the empty auditorium, the lamp burning low, pretending to read lines but really just listening for that soft, otherworldly voice. Each night, he wondered if the man would come, and each night, his heart pounded harder.

The man always came only when Femi was half asleep, waiting in anticipation. Femi was curious but too afraid to ask too many questions. It became an unspoken understanding between them.

There was something ritualistic about their meetings. Neither spoke more than necessary. Femi sometimes wondered if he was dreaming, but each morning, his voice was stronger, his lines more natural, and his fear a little deeper.

Even though Femi’s skills improved quickly under the man’s teaching, he became more and more uneasy. At that time, society emphasized collective spirit; nobody was allowed to keep secrets from the group.

The troupe leaders always said, “What one person knows, we all must know. If you hide something, e fit spoil for everybody.” Femi’s new talent drew praise, but also suspicion—how was he suddenly so good?

Femi had never seen the man when he was fully awake, but the skills he learned were real.

He tried to catch the man in the daylight, or ask around about him, but every trace vanished by sunrise. Only Femi’s new-found confidence and skill remained, a blessing mixed with dread.

In the end, Femi couldn’t handle the pressure anymore and told the troupe about it.

He gathered his courage and confessed everything one hot afternoon, hands shaking, voice barely above a whisper. The room fell silent, and even the most stubborn among them felt a shiver crawl up their spine.

At first, the troupe leaders thought he was joking, but Femi insisted, so they had to take it seriously.

“Femi, you sure say na wetin you see?” they asked. But his eyes told them all they needed to know—there was no joke here. The elders murmured among themselves, crossing themselves or muttering small prayers.

The leaders didn’t know what to do about such a thing, so they reported it to the local authorities.

They went to the council office at Mapo Hall, trying to sound calm, but their voices shook. The clerk they met at first tried to laugh it off—until he saw how serious their faces were.

The officers at first didn’t want to get involved—it all sounded too unbelievable. Who would believe such a story? But since the Ibadan Drama Troupe was a government institution and had officially asked for an inspection of their residence, which was a reasonable request, two officers were sent to check it out.

They sent the officers with a copy of the official request, stamped and signed in triplicate. “Go see what is worrying these theatre people,” the DPO said, shaking his head, but he sent them anyway. In Nigeria, even small wahala can turn big if you ignore it.

One of the officers was called Musa, an old hand who had stayed on from the original colonial police force after the city’s peaceful transition. With decades of detective experience, he was very familiar...

Continue the story in our mobile app.

Seamless progress sync · Free reading · Offline chapters